Audrius Stonys, Collected Posts on his Works

Myterne, legenderne, ritualerne, det er omkring det, jeg ser Stonys hele oeuvre dreje sig: det irrationelle, det uforklarlige, det spirituelle, det som ikke kan og ikke skal forklares. I utallige sammenhænge har jeg som ordstyrer ved filmforevisninger forsøgt at få ham til at forklare. Men altid stritter han imod de hurtige fortolkninger og konklusioner, hvor ord efter hans mening banaliserer den visuelle oplevelse og følelse, han ønsker at give sin tilskuer. Og hvorfor lige det klip og den overgang. Kunne det være fordi… måske, siger han, det er op til dig… (TSM)

THE BIG CENSOR INSIDE

Audrius Stonys made a lecture this morning. I have heard him doing so many times and have written several praising sentences on filmkommentaren.dk – about this filmmaker who is for sure to be considered as a national poet in his own country, and from a world perspective as an excellent representative of a different documentary cinema.

The biggest censors are inside yourself, Stonys said, who grew up in a country occupied by the big empire and who did not really see films in general geting better after the independence. He said so after another pleasant view of the 1978 Herz Frank film ”10 Minutes Older”. I truly believe that film is a conversation between equal partners, Stonys continued, the audience takes part in the creative process, this meeting is the most important part of the filmmaking.

I don’t believe in films without mistakes, he said and went on to show a clip from his own ”Flying over Blue Fields”, where a sport aeroplane lands on a field, a man gets out, parks the plane and goes inside while the camera observes chicken and bushes accompanied by music. No words, I don’t trust them, Stonys said, and showed another clip, from his early work, ”Earth of the Blind”, that has no words at all. I want to catch the impossible, he could also have said the invisible and the emotions in a face, like he demonstrated in the film from 2000, ”Alone”, a film in many layers: a girl that visits her mother who is in prison, a film crew that is (the director’s words) ”using” her, and an atmosphere of melancholy, a feeling that is present in most of Stonys films. He did not show films from recent years, he could have done so, and demonstrate that he can also cope with words as he did in ”The Bell”. (Post 25-06-2009 11:42:45 by Tue Steen Müller)

ANTIGRAVITACIJA (1995)

This Stonys film was made using the prize he received in 1992, the Felix Prize, for the best short film in Europe, Neregiu Zeme (World of the Blind). It was shown in Gudhjem that same year. In 1995, he returned with the result, a film about our longing to overcome what keep us on the ground.

For a long time, Stonys had wanted famous Lithuanian cinematographer Jonas Gricius to photograph a film for him. He finally succeeded. And what wonderful pictures! We are moved into the beautiful old tradition of large black-and-white 35 mm film sequences where every shot is considered down to the last detail. Stonys subsequently pursues this artistic deliberateness by putting every single scene into a perfectly harmonious context, whose authenticity I thoroughly accept. A soundless work. I have rarely experienced a film that leaves me so utterly incapable of objecting, of imagining other solutions. This film is definitively finished.

But what’s it really about? Like his previous films, Stonys portrays empathy. At the 1991 festival, he brought his film from 1989 called Atverti duris ateinanciam (Open the Door to Him Who Comes). Like Neregiu Zeme, it is photographed in the same dignified and old-fashioned manner, 35 mm film, black and white, features shared by subsequent films. With Harbour from the 1998 festival, he finally brings colour into his meditation on body and water. The film’s setting is public baths. Its plot is purification. It also describes a pastor in a remote parish who is visited by people, from large cities too, because of the peace of mind and answers the big questions he gives them. The other film portrayed people without sight in a world of sounds and dim contours, and changing degrees of light and darkness. Reflecting, almost wordless, states of mind. Dreaming, they yearn for existential relics. Dismal tones, will the project succeed?

Stonys’ manuscript for the gravitation film demanded that the crew had to shoot sequences for at least a year, because as a matter of course the scenes jump from snow-covered landscapes to sweltering village streets in spring, from spring floods to a sleigh in crunchy frost. And the young director pulled the fine old cinematographer, who here made his first documentary, up to heights, on roof scaffolding, on high railway bridges and at the very pinnacle of church towers. Because the pictures must show us how the world looks from these man-made structures reaching to the heavens. The film’s heroine is an old woman who forces her way up the longest ladder I have ever seen to the tip of the spire on the village church. At the very top she gazes out on summer landscapes. The next clip shows us, very correctly, the scene from her angle, but now it is in the bitter cold of winter. She climbs up there all year round. We don’t know why, she does it out of necessity. (Allan Berg Nielsen in Tue Steen Müller, ed.: Balticum Film & TV Festival 1990-99, Baltic Media Centre, 1999)

ALONE (2001)

A girl visits her mother in prison. That’s the story. The whole story. The girl sits on a bed in a room at her grandparents’ house. She says nothing.s nothing. She is in a car, her grandfather drives. She says nothing. They take a break and have a bite to eat at a highway café. She says nothing. She enters the prison and sits with her mother. No words.

Nothing really happens. You don’t get any explanations – what I have just told you is my interpretation. They must be her mother and her grandparents. Three generations gathered around an event, which we don’t know anything about. Why is the mother in prison? We are not told. It is not important.

The girl is important. The pace of the film is slow and insisting. The filmmaker wants you to look at the girl, to see her. A beautiful face, a dreamy look, yet sad maybe. What is she thinking of? What are her feelings? Is she scared? Of what? Maybe of taking part in a film and being shuffled around by the filmmakers, who are busy placing the camera in the car! ‘This is a film, we set the whole thing up, we want you to be aware of this fact,’ is what the filmmaker tells us. When the cameraman with his Arriflex appears in the picture, it creates a meta-level and a certain distance. The face of the child is not the face of a specific child, it is the face of a child. Music by Händel and Purcell accompanies this image. With a magnificently strong metaphor at the end of the film – the Tree of Life.

After a handful of short documentaries, Lithuanian filmmaker Audrius Stonys has, as (too few) festival connoisseurs know, positioned himself as a true poetic documentarist. With films like World of the Blind, Antigravitation, Harbour, Flying over Blue Fields and now Alone, he has left his unique signature on the short documentary genre. Though he has a much more romantic approach to reality and a more distinct narrative style, Stonys is the most obvious follower to the Armenian master Arvand Pelichian and his enigmatic film language demonstrated in Seasons. Stonys believes in the strength of the picture and prefers to avoid dialogue if possible. He knows how powerful and manipulative film can be. This is why he introduces the filmmaking aspect in this new film. He wants us to look at the face of the child. At innocence. That is what I read into this beautiful visual poem.

(Tue Steen Müller in Modern Times 2017)

UKU UKAI (2006)

The film starts in deathly silence. Make-up is carefully being applied to a woman’s face by another woman. Death in disguise? Is this about death? Are we death in disguise? All of us? Or does the first scene of the film also infuse our thoughts with the idea of closeness and distance? The closeness of the old woman, the distance of the young. To death. And their distance to each other. And then, at the end of this chain of thought, the alarming realisation: their closeness to each other. The long scene finally ends.

Death is a condition and a moment. Of silence. Life is a long-distance race. Surrounded by good advice and soft, noisy punchlines, “… just sit back and close your eyes / take a deep breath… / … breathe in and out / again, breathe in deeply …/ …and breathe out / listen to the sounds around you / accept them / become one with the environment,“ – he is running against time, for his life. In every respect, someone quite unlike the woman being made up. But his scene follows close on the heels of hers. Because they basically think alike, they are both struggling for life, pleasure, beauty. Audrius Stonys wants his films to gather lonely people who think alike into groups. This is his method of making films. And he has used it to make this one. The long-distance runner runs into the picture, through it and throughout the film. Against time.

Sleep is the living sister of death. Just before the woman in the third scene falls asleep (and also at that moment), her thoughts resemble the runner’s in the second. She surrenders to sleep as day to night, life to death. Confident of reawakening. Later on, awake again, she is jogging barefoot on her living-room carpet. The scene emphasises tactility, repetition, reality. In another scene, she is standing in front of the mirror, carefully applying night cream to her face. Revitalising it after removing her make-up. Working against time.

The film is indeed difficult, and we observe its relentless quest: to pursue the themes throughout the filmmaking. Like all auteurs, Stonys apparently works from film to film as if crafting a single work. In his lyrical, documentary meditations, the familiar motifs recur. His perception of time, of beauty and – starting with the etude Alone – he tests his art’s ability to endure in genres and idioms. To keep it from dying an early death, like nostalgia or aestheticism. Moralism or entertainment. Mainstreaming or consumerism. Which is why it requires such an effort for us to watch it. As Tarkovskij recalls what Goethe wrote, ”Reading a book is just as difficult as writing it!”. In other words, much remains to be done before we can truly claim to have watched Stonys’ film.

This is also the film’s major dilemma: it is so self-absorbed, we’re denied its reward; we become so accustomed to the way it jars our sensibilities that we all too easily abandon it instead of being taken in by it. Because we are not seduced, as in Earth of the Blind, by the beauty of Rimvydas Leipus’s magical black-and-white tapestry. Nor, as in Antigravitation, by the tension created by Jonas Gricius’s camerawork, drawing on an illustrious tradition (for which he gave his life). Will the old woman reach the top of the ladder? And if so, what will she do then? Nor, as in Harbour, by the fascination of travelling along an old wall in dignity, like the tired bodies in the public baths. And absolutely not, as in Alone, by the movement as the music infuses a dimension of measured infinity into the face of the grieving child on the back seat of the car.

As we watch Uku Ukai, we are once again robbed of retrospection’s comfort of convention. As in Countdown, where we were brutally and without warning delivered up to the aesthetics of television, here we are abandoned to the unique pictorial beauty of the TV commercial repeatedly disturbed by the ugly colours of sportswear. There’s no getting around it. The world has changed. Alone in brief silent night scenes of the city silhouetted against the sky, yes, and trees blowing against the same sky, yes, and a young dancer practising, yes, – leading our thoughts sadly back to the master, Henrikas Sablevicius, and his era. (Allan Berg Nielsen in DOX 2006)

THE BELL (2007)

The sixth film to be shown at the unique festival in Belgrade, starting tomorrow saturday, under the subtitle “European feature documentaries”, organised by Svetlana and Zoran Popovic and their team, and with me taking part in the selection is made by Audrius Stonys according to the old stories, written about 300 years ago, during the Lithuanian – Swedish war, the bell from the bell tower of Plateliai Church has been removed and taken off. It was carried away across the frozen lake, but the ice cracked near the Kastel island and the bell sank. One hundred years later a snorkeling expedition went on a search for the bell. It has been told that they found it, but for inexplicable reasons, they let it sink again. It has been told that the sound of a submerged bell can be heard from the lake’s depth. In the Summer of 2006, the film crew, along with a snorkeling team, went on a search for the legendary bell. This diving into the still water of the mythical lake was a motive for the search through the time dimension and through shady silhouettes of memory and ancient tales. Audrius Stonys penetrates behind the surface of reality and tries to transform simple actions into fantastic sights allowing us to take a glimpse into the methaphysical world.

Audrius Stonys has always remained faithful to himself and to his unique conception of cinema and a poetical interpretation of the world. He has probably won all the prizes worth winning, including the European Oscar, the Felix, but it has not made him less uncompromising in his film language. Or maybe it is better to call it film paintings! Watch ”The Bell” that can be seen as the director’s hymn to legends and irrationality. Or to the beauty of human creativity. (Post 25-01-2008 19:13:35 by Tue Steen Müller)

AUDRIUS STONYS OG THE BELL

Jeg har kendt Audrius Stonys siden begyndelsen af 1990’erne. Som andre baltiske filmfolk kom han til Bornholm til Balticum Film & TV Festival, som fandt sted i ti år med hovedsæde i Gudhjem. Ved de første festivaler drejede mødet med balterne sig om politik og historie. Verden havde ændret sig omkring 1990. Det sovjetiske imperium var faldet sammen, Berlin-muren var væk, og Estland, Letland og Litauen var blevet selvstændige republikker. Det var det, som filmfolket talte om. I al fredsommelighed og med kun få nationalistiske udfald.

Der var et væld af historier, som skulle fortælles og de fleste drejede sig om de sovjetiske overgreb på balterne – og om glæden ved friheden til igen at være sig selv, at kunne udtrykke sin mening og hylde sit land og dets kultur f.eks. gennem sangfestivalerne og andre samlende manifestationer.

Så der var ingen markante kunstneriske præstationer at lægge mærke til det første par år. Det ændrede sig hurtigt og for mig var det en fryd at kunne se unge talenter markere deres helt egen stil. Jeg fandt ud af, at der var stor forskel på de tre landes dokumentarfilmtradition, helt naturligt når man tænker på de meget forskellige udgangspunkter, landene havde haft tilbage i tiden før den sovjetiske besættelse. Nok var der kraftig censur i USSR, men de lokale statslige filmstudier havde en vis bevægelsesfrihed og fremragende dokumentarfilm var blevet skabt i såvel Tallinn, Riga som Vilnius. Vi havde set nogle af dem, men alt for få. Det blev der rådet bod på i løbet af de 10 år festivalen varede og for mit vedkommende også siden da.

Audrius Stonys og hans kammerat Arunas Matelis kom tll Bornholm med en film, der skildrede den smukke kæde af hænder, der blev formet fra Estland i nord til Litauen i syd. Det var den rene eufori, som bar denne menneskekæde og dette udtryk for solidaritet. Som Stonys har udtrykt det, ”alle kameraer ville fange disse første frihedens åndedrag”. ”Baltic Way” hed filmen, som er 10 minutter lang og var instruktørens første og formentlig også sidste direkte politiske kommentar. I det hele taget var alle Stonys film fra 1990’erne kortfilm, optaget på 35mm materiale med henblik på at blive vist i biografer og på festivaler.

I 1992 fik han så sit internationale gennembrud med filmen ”Earth of the Blind” og i en alder af 26 år fik han den fornemste europæiske filmpris, Felix, uddelt af tv-stationen arte, for bedste europæiske dokumentarfilm. Filmen blev også vist på Bornholm, og Stonys blev en af festivalens faste gæster. Jeg var med til at arrangere festivalen og siden begyndelsen af 1990’erne har han været en god ven, hvis kunstneriske udvikling, jeg har kunnet følge tæt på, og hvis internationale karriere jeg har kunnet skubbe på gennem retrospektiver på forskellige festivaler og gennem at få ham ansat på European Film College i Ebeltoft, hvor han var dokumentarlærer i et år i begyndelsen af dette årtusinde. Stonys er nu en ofte brugt lærer på workshops i og udenfor Europa, han har en stor filmviden og det har været vigtigt for ham at videreføre sin læremester Henrikas Sablevicius arbejde som mentor for yngre filmfolk. Sabelivicius var vor mand i Vilnius, når vi tog dertil for at vælge film ud til festivalerne. En fremragende dokumentarist som holdt fast i dokumentarfilmen som et kunstnerisk udtryk og undgik at lave propagandafilm, som mange af hans jævnaldrende gjorde under USSR-tiden.

I sommeren var min kone og jeg i Litauen, jeg for at vælge film til Leipzigfestivalen, men vi var der også for at holde nogle dages feries med familierne Stonys og Matelis. Vi blev taget ud til kysten, kørte rundt i de Sahara-agtige dunes, som så ofte har været en kulisse i litauiske film. Stonys tog os til sine locations, vi aflagde et besøg ved Sablevicius grav, og mødte nogle af personerne fra hans 15 film, som alle er optaget i hans land.

Det er det, som jeg kender til, det er hvad jeg er en del af, den kultur og det sprog, som jeg elsker, har altid været svaret, når jeg har spurgt ham, hvorfor han aldrig har optaget udenlands.

Et af de steder, vi besøgte på vores Litauiske rundtur, var søen Plateliai, rammen om ”The Bell”, og stedet hvor der angiveligt skulle ligge en kirkeklokke, i følge de mange historier, der florerer herom. Men om ”The Bell” i virkeligheden handler om om noget helt andet, vil jeg lade stå et øjeblik. Det er ihvertfald klart ret tidligt i filmen, at der er ikke er tale om en reportageagtig dokumentar a la National Geographic, hvor plottet er: finder de klokken eller ej?

Ikke desto mindre sender instruktøren et hold dykkere ned på søens bund for at kigge efter klokken, samtidig med at instruktøren tager rundt til folk i regionen for at spørge dem om de har hørt noget. Om den forsvundne klokke. Det er der mange, der ikke har og nogle, der har. Der var vist noget om… er et svar, der dukker op.

Stonys spiller med tre elementer i denne film, der som ”Countdown” er usædvanlig både i forhold til længde og i forhold til den ordmængde, den indeholder. Han bruger interviewet, han bruger fortællingen om dykkerne der gør klar til og går ned under vandet og han bruger arkivmateriale, der fortæller om den folkelighed, der har udfoldet sig og stadig udfolder sig omkring søen. I dag er der rockkoncerter, tidligere var der andre former for fester, ofte knyttet til religiøse helligdage.

Der er ingen faste fortællestrukturer i ”The Bell”, som der aldrig har været hos Stonys. Det virker som om han konstant bliver nødt til at dvæle ved en ny opdagelse eller reflektere over det materiale, som hans fotograf har givet ham. Når han går fra nutid til datid til undervandsbillederne, er der ingen speciel dramaturgisk logik, der er blevet fulgt. Og det er tydeligt at han bliver mere og mere optaget af at arbejde med arkivmateriale, hvilket kommer til fuldt udtryk i hans seneste film ”Four Steps”, som er en reflektion over kærlighedens vilkår med udgangspunkt i bryllupsritualer, som de har udspillet sig over fire årtier.

Myterne, legenderne, ritualerne, det er omkring det, jeg ser Stonys hele oeuvre dreje sig: det irrationelle, det uforklarlige, det spirituelle, det som ikke kan og ikke skal forklares. I utallige sammenhænge har jeg som ordstyrer ved filmforevisninger forsøgt at få ham til at forklare. Men altid stritter han imod de hurtige fortolkninger og konklusioner, hvor ord efter hans mening banaliserer den visuelle oplevelse og følelse, han ønsker at give sin tilskuer. Og hvorfor lige det klip og den overgang. Kunne det være fordi… måske, siger han, det er op til dig.

Kameraarbejdet er alfa og omega for Stonys, som altid har valgt sine fotografer med stor omhu. Det er indlysende, at hans reference er den russiske tradition for den visuelle fortælling og når jeg har presset ham til at nævne sine inspirationer, kommer han altid tilbage til armenerne Paradjanov og Pelichian, og naturligvis kan han sin Tarkovski forfra og bagfra og er langt bedre til at komme ind i dennes værker med alle de for os svære religiøse henvisninger.

Tilbage til strukturen i ”The Bell”, den ulogiske, hvor det ofte virker som om instruktøren glemmer filmens mål og indledende hensigt (er der en klokke på søens bund?) og falder i visuel svime over den skønhed, som materialet indeholder.

Den gamle dame, der besværet går sin tur til det lille klokkehus… langsomt med horisonten bag sig, krumbøjet er hun der og viser tilbage til andre gamle kvinder, som lader klokkerne give musik fra sig, f.eks. i ”Antigravitation”, et af Stonys hovedværker, hvor man bliver helt svimmel ved at se den gamle dame stige op i klokketårnet.

Der er lange sekvenser af den slags i ”The Bell”, som bevæger sig fra at være meget konkret og interviewpræget – ”har I hørt at der skulle være en klokke på søens bund” – til at være en udforskning af den verden, som findes under vandet, en paradisisk jungle som den visualiseres i billeder, der minder mig om surrealisten Yves Tanguy og hans drømmebilleder.

Man må være logisk, siger en dame i filmen, selvfølgelig er der ikke en klokke under vandet, så var den jo fundet for længe siden, man børnene har en anden opfattelse, nogle af dem har faktisk set klokken.

Og Audrius Stonys har en anden opfattelse, denne fine kunstner som er helt sin egen og som stadig søger nye veje, men altid indenfor sin egen kulturkreds blandt de mennesker, han holder af og hvis historier og sange han aldrig bliver træt af at høre.

Det er så fortjent at Stonys bliver hilst på som den litauiske nationalpoet, han er. (Tue Steen Müller, introduktion til foredrag 13. marts 2009 i FOF, Randers)

FOUR STEPS

… My host in Lithuania, a name I mention with much respect and admiration is Audrius Stonys, who makes one film per year, always related to the culture and traditions of his native country, always challenging to watch, born out of humanistic thinking. This time the title is “Four Steps”, made out of a deep fascination of super-8 mm wedding films, shot in 1961, 1972, 1983 and 2007. And of course it is not “only” about wedding traditions, it is also philosophy and literature and songs and music. I look forward to see this film for the third time! (From a post 29-07-2008 09:17:34 by Tue Steen Müller)

RAMIN (2010)

Audrius Stonys deserves much praise for his ”Ramin”, a film about an old man in Georgia, his daily life, his attachment to his late mother, his looking for a woman he knew in his youth… the story is told in stunningly beautiful images by Audrius Kemezys, the story construction is complicated, but there are magical moments (like in most of Stonys films) that you will never forget, and original ideas. In this one it is a cross-cut from a loong celebration of Ramin’s birthday to a cat crying outside the house with a nice warm hen to lean on! (From a post 02-07-2011 22:01:28 by Tue Steen Müller)

The festival in Vilnius 2011 (September 22 – October 2) opened with the newest film by local master Audrius Stonys, ”Ramin”, produced by Vides Film Studio in Riga, Latvia. The fllm (not in the Baltic competition) is a both touching and amusing portrait of an old man (Ramin), who has been a fighter (wrestler) his whole life and now (as the catalogue says) fights the old age loneliness. Magnificent camera work and the courage to let scenes grow reminds us how important a film poet Stonys is. (Post 29-09-2011 by Tue Steen Müller)

LITHUANIA

… is a Baltic country, the most southern, and the most exciting when it comes to documentaries.

They are mostly short and based on images – the Lithuanian documentarians compose the image and treat the spectator as an intelligent person. The information needed to understand a story or a problem or a complex thematic issue is conveyed by the combination of image and sound and montage. In other words, they make FILMS and are still relatively “innocent” when it comes to adapt to television standards.

“They” are directors like Audrius Stonys and Arunas Matelis and Oksana B. and Rimantas Gruodis. I have just been there to watch new films to be recommended to Leipzig Film Festival to which I offer scouting services. If any reader of this would like to have contact with the Lithuanian filmmakers, you can google Stonys and Matelis, who both have their own websites and will direct you to where to get hold of dvd’s. (Post 12-08-2007 by Tue Steen Müller)

INTERVIEW

I have written – and so has Allan Berg – many times about Lithuanian documentary poet Audrius Stonys, who by the way is a big admirer of the films of Jørgen Leth, who is on the cover of filmkommentaren.dk for the moment. At the University of Pompeu Fabre in Barcelona, a student made an interview with Stonys, 8 minutes long and placed it on YouTube: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vjbl6cb7dko (Post 20-09-2008 by Tue Steen Müller)

DOCALLIANCE

For 2.5€ in total you will be able to watch three great films by Lithuanian documentary poet, Audrius Stonys, who is “the event of the week” of the brilliant vod.

The films are Uku Ukai (2006), Countdown (2004) and Ramin (2011). DocAlliance has made a small talk with the director:

The acclaimed director Audrius Stonys ranks among the most prominent Lithuanian documentary filmmakers. According to Stonys, the issue of freedom plays the main part in cinematography, being more important than any aesthetic criterion. Especially as there still are attempts to restrict such freedom, only they have taken the form of dictatorship of money. Stonys believes that documentary filmmaking was not born out of the desire to provide information. It was born out of astonishment and the possibility of being able to stop time and contemplate the miracle called “the world”.

In response to a seemingly perplexing question: “Who makes your films?” Stonys said: “Recently, I visited a doctor because I had problems with my back. And for only fifteen minutes of work he asked for a lot of money. Sure, he fixed me up, but he is my friend. So I wondered why the heck he was asking so much. This is what he said: ‘Look, those fifteen minutes contained all the years of my practical training, all the books I have read plus the experience of my professors who have shared their knowledge with me.’ And my films are also the result of the work of many souls.” (Post 18-02-2013 by Tue Steen Müller)

AUDRIUS STONYS OG FILMKOMMENTAREN.DK

Jeg satte for nogen tid siden dette still ind som nyt gruppebillede på Filmkommentarens Facebookside. Sevara Pan så straks, at det måtte være fra en film, og spurgte fra hvilken, og Tue Steen Müller synes, jeg skal rykke ud med hele historien. Den er så her. Billedet er fra Ensom (Viena / Alone), 2001, 16 min. af Audrius Stonys fra Vilnius. Filmen er fotograferet af Rimvydas Leipus.

OM FILMKOMMENTAREN

Da vi begyndte august 2007, skulle grafikeren, som lavede vores blog, have et visuelt forlæg. Vi valgte dette still fra Stonys film, scenen, hvor den lille pige i en travelling går langs fængslets mur hen mod porten for at blive lukket ind til sin mor. På besøg.

Grafikeren brugte murens struktur, som herefter minder os om adskillelse og menneskets tilværelse og ensomhed i den og, ved vi, som har set filmen, skønheden og glæden i kærlighedsmødet. Filmkommentaren indrømmer noget sent lånet af disse fotos og krediterer på det taknemmeligste Rimvydas Leipus og Audrius Stonys for deres definition af vores filmkunstneriske profil. Som vi gør, hvad vi kan, for at leve op til.

OM FILMEN

Den handler om cinematografiens sublime evne til at skabe en mere virkelig virkelighed. Jeg plejer at se den som en etude, på én gang et katalog over en række filmiske greb og så også en ganske lille gribende og smuk fortælling om ubodelig ensomhed. Fortællingen rives hele tiden i stykker ved det Brechtske verfremdungsgreb (husk, dette er film…), men derved understreges alene fortællingens og filmens styrke.

OM INSTRUKTØREN

Han begyndte at skrive og at lave film, da Litauen var en del af Sovjetunionen, og han har siden som uafhængig filminstruktør og producent lavet 14 film. Hans film har vundet adskillige internationale filmpriser. 2004-2005 var Stonys lærer i dokumentarfilm på filmhøjskolen i Ebeltoft. Siden 2006 har han undervist på Tokyo Waseda Universitet. Audrius Stony er af den overbevisning, at frihed i film er det centrale, det er vigtigere end nogen æstetisk opfattelse. Særligt når der har været forsøg på at begrænse denne frihed har det vist sig, at filmene kun har ændret deres ydre skal. Dette synes at være særligt tydeligt i dokumentarfilmene, som forsøges presset ind i en standard ramme af en slags produktion af information, underholdning, følelser og undervisning. I modsætning til dette mener Stonys, at dokumentarfilmen ikke er sat i verden med ønsket om at informere. Den er født af undren med opdagelsen af muligheden for at standse tiden og fordybe sig tænksomt i tilværelsens mirakel. (Written 14-04-2014 by Allan Berg Nielsen, efter http://dafilms.dk/ hvorfra flere af hans film kan streames)

GATES OF THE LAMB (2015)

Stonys asked me some time ago what I thought of ”Gates of the Lamb” and its festival potential. These were my words:

This film, which is visual, have very few words, uses music, has no “story” as such but lets us enjoy Faces Faces Faces, mostly in profile at the right part of the image – great cinematography – and music and a solemn atmosphere with fine small humoristic sequences with children with open faces not really understanding, and yet… what is going on. You are back to a world that you master to convey.

I have no information if “Gates of the Lamb” has been to other festivals so far, but to have it here in the hometown of the director is an obvious choice. (TMS 13.09.15 in a post on Vilnius Festival)

VILNIUS 2015

The winners of Vilnius Documentary Film Festival Baltic competition have been appointed and the top two were from the hosting country:

Veteran Audrius Stonys took the first prize for his “Gates of the Lamb” that I have written the following words about: This film, which is visual, have very few words, uses music, has no “story” as such but lets us enjoy Faces Faces Faces, mostly in profile at the right part of the image – great cinematography – and music and a solemn atmosphere with fine small humoristic sequences with children with open faces not really understanding, and yet… what is going on. Audrius Stonys is back to a world that he masters as noone else.

Giedre Zickyté took the second prize for her ”Master and Tatyana” that I have written the following words about: So, there it is, the film about the Lithuanian photographer Vitas Luckus (1943-1987), his life, his art and first of all his love story with muse and wife, Tatyana. It is made by Giedre Zickyte, who has been working on it for years. I heard about it five (maybe more) years ago, when she was pitching the film at the Baltic Sea Forum, and since then I have had the pleasure to watch sequences and rough versions. Yes, pleasure, because Giedre Zickyte has kept the passion for her film the whole way through, and pleasure because you can see Quality, high Quality in the final film. For me it’s brilliant, nothing less… the whole review, click: http://vdff.lt/en

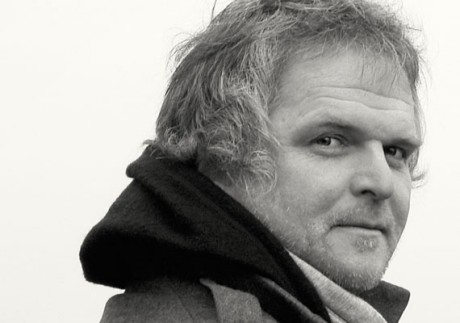

The photo of Audrius Stonys thanking for the main award is taken from the FB page of the festival – © Mindaugas Česlikauskas (Posted 28-09-2015 by Tue Steen Müller)

THE TRUTH OF LIFE

… this is just a natural thing in documentary filmmaking, the moment you think you know everything and it only remains to capture your “discoveries”, the truth of life takes over and turns against you. So, I let my visions be transformed. The essence lies in the quest. Subsequently, the films will live the lives of their own….

Says Audrius Stonys in an interview on cineuropa, very well made by Aukse Kancereviciute. I recommend you to read it all, here is a taster:

The film Ūkų ūkai emerged from a desire to expose the beauty industry, but in the course of shooting your attitude changed radically. Does it often happen that life adjusts preconceived visions?

Perhaps not a single one of my films was unaffected by this. The idea changes, because reality turns it upside down and destroys it. At first I was very frightened; it seemed to me that was it – that was the end. I had an idea and everything took another turn. Then I understood that this was supposed to be so. None of my films are as I originally conceived them. In Ūkų ūkai both the theme and the characterchanged. Instead of a strong, healthy, young man who goes swimming every day irrespective of whether it rains or snows, we have a tiny old woman tip-toeing across her room. Alone (Viena) was supposed to be about a girl who is going to visit her mother, who is in prison, and talking what she sees and feels, but instead I made a completely silent film. New Martyrology (Tas, kurio nėra) was supposed to show a man who died unbeknownst to anybody, but instead the Lithuanian film director Augustinas Baltrušaitis, whom fate and circumstances tossed into complete oblivion, became the protagonist of the film. When shooting Cenotaph it seemed that the film was about the meaning of reburial, but it turned out to be about meaninglessness. The initial concept is therefore diametrically opposite… (Posted 25-04-2016 by Tue Steen Müller)

http://cineuropa.org/it.aspx?t=interview&l=en&did=307560

Yes, it started yesterday, the fabulous documentary event in Amsterdam and today it’s all over with screenings, masterclasses, the academy, some films are in competition, others are not, facebook is full of ”come and see my film”, there will be many full houses. And many who prepare their pitches for the Forum. With meetings and parties.

I am not there this year for family and friend reasons – birthdays – but I have seen some of the films already so comments will arrive on this site, don’t have time for longer reviews but I will pick some films via links and Docs for Sale. So check it out – there could be recommendations you want to follow.

For instance the world premiere tonight of Audrius Stonys’ new film

– yes we love him here on filmkommentaren and have done so since his debut at the beginning of 1990’es. The title is ”Woman and Glacier” and this is what I wrote to the director, when I had seen the film:

“…Magic, Audrius, mind-blowing to be there, … Will watch again, it brings me in a meditative mood, love the way you use archive and the structuring with the musician. Thanks for letting me watch – on a computer… you will have a lot of success with that film…” and later on, ”… this quote from Swedish Sune Jonsson in 1978 fits well to your film, especially the last words “inner landscapes”: “…A documentary work is not intended for the esthetic connoisseur or the preoccupied consumer, but rather for people in vital need of increasing their knowledge: of transforming communicated environments, epochs, nature scenes into personal experiential substance – something with which to enrich their own inner landscapes.”

The IDFA website short description of the film: A filmic ode to a woman’s choice to live in solitude. For 30 years, a Lithuanian scientist has been conducting climate research at the Tuyuksu Glacier in Kazakhstan.

New (almost) wordless masterpiece by Audrius Stonys with his genius cameraman Audrius Kezemys. (Posted 17-11-2016 by Tue Steen Müller)

POSTS IN DANISH

De oprindelige dansksprogede versioner til to af teksterne ovenfor:

ANTIGRAVITACIA (1995)

Stonys film blev lavet for præmien, han modtog i 1992, Felix¬prisen, for bedste kortfilm i Europa. Den hed Neregiu Zeme (World of the Blind) (Den blindes verden), og den blev vist i Gudhjem samme år. I 1995 kunne han så præsentere resultatet, en film om længslen efter at overvinde, hvad der holder os ved jorden.

Stonys havde meget længe ønsket at få den berømte russiske fotograf Jonas Gricius til at fotografere en film for sig. Det var så lykkedes denne gang. Og hvilke billeder! Vi flyttes ind i den smukke, gamle tradition af store sorthvide 35 mm filmscener, hvor hver enkelt optagelse er overvejet til mindste detalje. Denne kunstneriske velovervejethed følger Stonys herefter op, så hver enkelt scene fuldstændig harmonisk sættes på plads i en sammenhæng, som jeg er overbevist om, ikke kan være anderledes. Et lydefrit værk. Sjældent har jeg oplevet en film, hvor jeg i den grad er ude af stand til at komme med indvendinger, ude af stand til at forestille mig andre løsninger. Den her film er lavet helt færdig.

Men hvad handler den så egentlig om? Som i de tidligere, skildrer Stonys kontemplativiteten. På festivalen i 1991 havde han sin film fra 1989 med. Den hedder Atverti duris ateinanciam (Open the Door to Him, who Comes). Både den og Neregiu Zeme er fotograferet på samme værdige og gammeldags måde, 35 mm film, sort/hvid. Sådan også med de senere. Først Harbour fra festivalen 1998 tager farvefilmen ind i sin meditation over kroppen og vandet. En badeanstalt er filmens sted. Renselsen dens handling. Den tidlige er om en præst i et afsides sogn, som søges af mennesker også fra de store byer, fordi de hos ham, i hans kirke, finder fred i sindet og svar på de store spørgsmål, og den anden film fortalte om mennesket uden syn i en verden af lyde og svage konturer, vekslende lys- og mørkegrader. Tilstande i eftertanke, ordløse næsten. Drømmende søger de tilbage mod eksistentielle relikter, vemodige i tonen, vil projektet lykkes?

Antigravitacija

Stonys manuskript til tyngdekraftfilmen har krævet, at holdet har måttet lave optagelser gennem i hvert fald et år, for der klippes som en selvfølge fra snedækkede landskaber til summende forårsvarme landsbygader, fra tøbruddets oversvømmelse til en kane i knirkende frost. Og den unge instruktør har hevet den fine, gamle fotograf op i højder, på tagstilladser, på høje jernbanebroer og allerøverst i kirketårne. For billederne skal fortælle, hvordan verden tager sig ud fra de himmelsøgende indretninger, mennesker konstruerer. Filmens heltinde er en gammel kvinde, som forcerer den længste stige, jeg mindes at have set, til det øverste i landsbykirkens spir. Helt oppe kigger hun ud i sommeren. I næste klip ser vi hendes syn, helt efter bogen, men det er bidende vinter. Året rundt, livet igennem klatrer hun den tur. Uvist hvorfor, men nødvendigvis må hun klatre. (Allan Berg Nielsen i Balticum Film & TV Festival 1990-99, red.: Tue Steen Müller)

Antigravitacija

UKU UKAI (2006)

Der er ganske tyst i filmens begyndelse. En kvindes ansigt sminkes omhyggeligt af en anden kvinde. Er det et sminket lig? Handler det om døden? Er vi sminkede lig? Alle? Eller bygger den første scene i filmen også nærheden og afstanden ind i vores tanke? Den gamle kvindes nærhed, den unge kvindes afstand. Til døden. Og deres afstand til hinanden. Og så ved tankerækkens slutning alarmlyden af overraskelse: Deres nærhed til hinanden. Scenen er lang, men den er slut nu.

Døden er en tilstand og et øjeblik. I tavshed. Livet er et langdistanceløb. Omgivet af gode råd af blide, larmende punch-lines: ”.. let’s sit easily and close the eyes / take a deep breath in… / … and out / again a deep breath in / …and out / listen to the noises around you / accept all the noises / be in harmony with the environment “ løber han imod tidens retning, løber han imod livets retning, for livet. I ét og alt forskellig som person fra kvinden, som sminkes. Men hans scene kommer lige efter hendes. For de tænker grundlæggende ens, kæmper for livet, nydelsen, skønheden. Audrius Stonys vil i sine film bringe de ensomme mennesker sammen. I grupper som tænker ens. Sådan vil han lave film. Og sådan har han lavet denne. Langdistanceløberen løber i billedet, gennem billedet, igennem filmen. Mod tiden.

Søvnen er dødens levende søster. Lige før kvinden i tredje scene falder i søvn (også i det øjeblik), tænker hun som løberen i anden scene. Hun overgiver sig til søvnen, som dagen overgiver sig til natten, som livet til døden. I trygheden om genkomsten. Senere, vågen igen, løbetræner hun rundt i sin stue på bare fødder mod tæppet. Scenen fastholder det taktile, gentagelsen, det konkrete. I en anden scene smører hun stående foran sit spejl omhyggeligt natcreme i ansigtshuden. Giver den liv efter at have fjernet sminken. Arbejder mod tiden.

Filmen er vel uomgængelig, vi følger dens konsekvens, som er at forfølge linjerne i hele filmarbejdet. Som alle auteurs arbejder Stonys tilsyneladende fra film til film på ét eneste værk. Motiverne er genkommende i hans lyrisk dokumentariske meditationer. Det er tidsopfattelsen, det er skønhedsopfattelsen, det er fra og med den fuldkomne etude Alone også at afprøve kunstartens overlevelsesmulighed i genrer og greb. Så den ikke dør ung som nostalgi og æstecisme. Moralisme og underholdning. Mainstream og konsum. Og det er derfor et arbejde for os at se den. Som Tarkovskij citerer Goethe for at have skrevet, at det er lige så stort et arbejde at læse en bog som at skrive den! Vi har således langt igen før, vi har set Stonys film.

Filmens store problem er da også, at den så koncentreret om sig selv forholder os belønningen, vi var vænnede til, at den støder ind i spørgsmålet om smag, så vi meget let forlader den frem for at suges ind i den. For vi forføres ikke som i Earth of the blind af skønheden af Rimvydas Leipus’ sorthvide magiske billedtæppe. Ikke som i Antigravitation af spændingen, som Jonas Gricius med sit kamera fra den store tradition (og med livet som indsats) leverer. Når den gamle kvinde mon op til toppen af den stige? Og hvad så deroppe? Ikke som i Harbour fascinationen ved en travelling langs en gammel mur i værdighed lig de trætte kroppe i badene. Og slet ikke som bevægelsen i Alone, lige da musikken lægger sit lag af præcis uendelighed på det sorgramte barneansigt der på bilens bagsæde.

Alone

Når vi ser Uku Ukai er vi atter berøvet de bagudskuende konventioners komfort. Som vi uforberedte i Countdown brutalt blev overgivet til tv-æstetikken, er vi nu prisgivet reklamefilmens særlige billedskønhed, ofte forstyrret af sportstøjets grimme farver. Der er ingen vej uden om. Verden er forandret. Alene i korte, tyste nattebilleder af byens profil mod himlen, ja, og træer i blæst mod samme himmel, ja, og en ung danser, som øver sig, ja – føres vores tanke vemodigt bagud mod mester Henrikas Sablevicius og hans tid. (Allan Berg Nielsen i DOX 2006)