Latvia: Award winners Lielais Kristaps 2026

I have copied from a press release:

“On Sunday, March 1, the National Film Award “Lielais Kristaps” ceremony took place at the Riga Congress Hall, honoring the best Latvian films and outstanding film professionals of the past year, as well as presenting special awards. A total of 25 awards were presented at the ceremony, along with three special awards and the Lifetime Achievement Award, which was received by Uldis Jānis Veispals — an outstanding stunt performer and one of the pioneers of professional stunt work in Latvia and the Baltics…

The National Film Award Lielais Kristaps is organized by the Latvian Filmmakers Union in cooperation with the National Film Centre of Latvia and the Ministry of Culture, with support from Riga City Council, the LMT Group, and Hannu Pro, in collaboration with the Riga Congress Hall, the National Archives of Latvia, Cinevera, Valmiermuiža, Wellton Hotels, Mārtiņš Bakery, Alkoutlet, and Illy. Media partners include LTV, LSM, Santa, Radio SWH, SWH TV, Kino Raksti, Kurzemes Radio, LETA, and the magazine IR.

The nominees of the National Film Award were evaluated by an international jury — Ilka Matila (Finland), Zane Valeniece (Latvia), Marge Liske (Estonia), Juris Poškus (Latvia), Guna Zariņa (Latvia), and Marija Razgute (Lithuania), representing extensive professional experience in film production, directing, distribution, media management, and international cooperation…”.

In a previous post on this blog I had a focus on the documentaries nominated – https://filmkommentaren.dk/lielais-kristaps-latvian-national-film-awards-2025/

… and I wrote short notes on those, who now have been awarded:

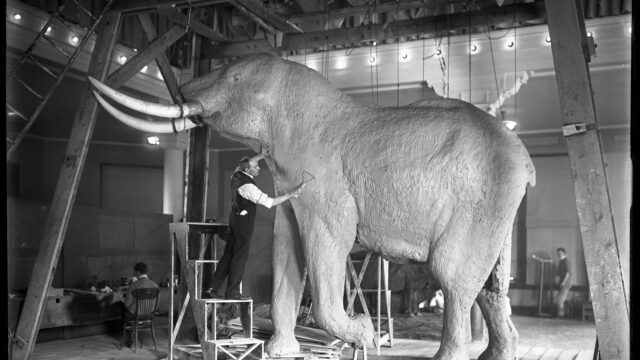

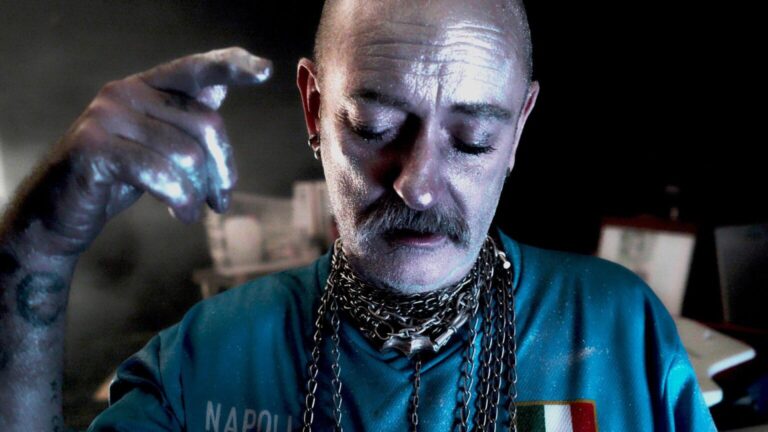

“Art Born in Agony,” dir. Elizabete Gricmane, Ramunė Rakauskaitė, prod. Uldis Cekulis, VFS Films, co-prod. Arūnas Matelis, Studio Nominum (Lithuania). Juris Kulakovs, national legend, composer and musician is followed closely by the young director Elizabete Gricmane in playful sequences. Charismatic he is Kulakovs, who passed away in 2024. PHOTO.

“All Birds Sing Beautifully”, dir. Krista Burāne, prod. Ilze Celmiņa, Paula Jansone, “VFS Films”. I saw it today and I will use the same word, playful, entertaining and thoughtful as this quote says (Letterboxd): “In the beginning there was the forest. Then came the live performance, and then the film. The yellow wagtail, Eurasian skylark, white-backed woodpecker, corncrake and hazel grouse have not only gotten their voices back, but have taken on human form — clad in elegant tailcoats and bearing names — to recount ancient tales…” Beautiful singing, great cinematography of all the birds.

And I complained that Laila Pakalnina’s “Scarecrow” was not nominated as Best Documentary Film BUT the film got two awards, anyway, these two: Paulius Kilbauskas, Vygintas Kisevičius (Scarecrows / Putnubiedēkļi) (Best Composer) and Māris Maskalāns (Scarecrows / Putnubiedēkļi) (Best Documentary Cinematography).

Here is the list of all winners:

Best Film

Red Code Blue / Tumšzilais evaņģēlijs (dir. Oskars Rupenheits, prod. Sintija Andersone, KEF Studija; co-prod. Roberts Vinovskis, Vino Films; co-prod. Antra Cilinska, Jura Podnieka Studija)

Best Feature Film

Escape Net / Tīklā. TTT leģendas dzimšana (dir. Dzintars Dreibergs, prod. Dzintars Dreibergs, Marta Romanova-Jēkabsone, Arta Ģiga, Inga Praņevska, Ilona Bičevska, Kultfilma)

Best Feature Documentary

All Birds Sing Beautifully / Visi putni skaisti dzied (dir. Krista Burāne, prod. Ilze Celmiņa, Paula Jansone, VFS Films)

Best Short Film

Slush / Žļurga (dir. Aivars Šaicāns, Jēkabs Okonovs, prod. Elza Siliņa, Daiga Livčāne, LKA National Film School; co-prod. Pilna)

Best Series

The Collective / Kolektīvs (Season 2), (dir. Juris Kursietis, Rūdolfs Gediņš, Ance Strazda, Artūrs Zeps, Roberts Kuļenko, Jānis Ābele; prod. Māris Lagzdiņš, Lelde Troska, Fon Films; co-prod. Latvijas Mobilais Telefons)

Best Minority Co-production

Solo Mama / Solomamma, (dir. Janicke Askevold; prod. Gary Cranner, Rebekka Rognøy, Magnus Nygaard Albertsen, Magne Lyngner, Bacon Pictures (Norway); co-prod. Inese Boka-Grūbe, Gints Grūbe, Mistrus Media (Latvia); co-prod. Viktorija Rimkute, Gabija Siurbytė, Dansu Films (Lithuania); co-prod. Jani Pösö, It’s Alive Films (Finland))

Best Debut Film

The Rider’s Voice / Jātnieka balss (dir. Iveta Auniņa, prod. Sandijs Semjonovs, Iveta Auniņa, Nora Luīze Semjonova, SKUBA Films)

Best Student Film

My First Funeral / Manas pirmās bēres (dir. Līva Klepere, prod. Grēta Grebže, Elza Siliņa, LKA National Film School)

Best Screenwriters

Ivo Briedis, Raitis Ābele, Lauris Ābele, Harijs Grundmanis (Dog of God / Dieva suns)

Best Director (Feature Film)

Oskars Rupenheits (Red Code Blue / Tumšzilais evaņģēlijs)

Best Cinematographer (Feature Film)

Mārtiņš Jurevics (Lotus)

Best Actress in a Leading Role

Agnese Budovska (Escape Net / Tīklā. TTT leģendas dzimšana)

Best Actor in a Leading Role

Raitis Stūrmanis (Red Code Blue / Tumšzilais evaņģēlijs)

Best Supporting Actress

Leonarda Ķestere (Flesh, Blood, Even a Heart / Nospiedumi)

Best Supporting Actor

Gatis Maliks (Flesh, Blood, Even a Heart / Nospiedumi)

Best Production Designer

Toms Jansons (Red Code Blue / Tumšzilais evaņģēlijs)

Best Costume Designer

Sandra Sila (Escape Net / Tīklā. TTT leģendas dzimšana)

Best Makeup Artist

Elīna Gaugere (Red Code Blue / Tumšzilais evaņģēlijs)

Best Documentary Director

Elizabete Gricmane, Ramune Rakauskaite (Art Born in Agony / Mākslas darbi rodas mokās)

Best Documentary Cinematographer

Māris Maskalāns (Scarecrows / Putnubiedēkļi)

Best Animation Directors

Raitis Ābele, Lauris Ābele (Dog of God / Dieva suns)

Best Animation Artist

Harijs Grundmanis (Dog of God / Dieva suns)

Best Composer

Paulius Kilbauskas, Vygintas Kisevičius (Scarecrows / Putnubiedēkļi)

Best Sound Director

Aleksandrs Vaicahovskis (Escape Net / Tīklā. TTT leģendas dzimšana)

Best Editor

Armands Začs (Flesh, Blood, Even a Heart / Nospiedumi)

![DIRECTOR'S CUT [WT]](https://cphdox.dk/wp-content/uploads/2026/01/1937206-640x360.jpeg)