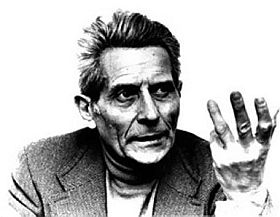

Georges Franju

A great director, not very well known today, but for this film blogger his “Le Sang des betes” (1949, 22 mins.) from a slaughterhouse in the Parisian suburb, is a unique masterpiece in the history of documentary films. The film can be bought through Aamazon or watched in different language version on YouTube. If you happen to be in Donostia late September, you will able to see more of Franju’s oeuvre. This is taken from the site of the festival in San Sebastian:

French filmmaker Georges Franju is to be the subject of one the retrospectives programmed for the 60th San Sebastian Festival to take place from 21-29 September 2012.

Georges Franju (12-4-1912 / 5-11-1987) was an enormously influential figure in French film culture. In 1936 he founded the Cinémathèque Française with Henri Langlois. His career as a director began in 1949 with documentaries, a field to which he contributed some of the greatest titles ever in the genre. His early works – Le Sang des bêtes, Hôtel des Invalides and En passant par la Lorraine – already demonstrated his particular talent for filming reality from unexpected angles, a trait leading in these testimonial films to a sensitivity akin to surrealism and expressionism.

Franju’s obsession with putting his finger on the inexpressible poetry of things through his lens stayed with him as he moved on to feature films with La Tête contre les murs (Head Against the Wall,1958), followed by Les Yeux sans visage (Eyes Without a Face,1959), considered to be a masterpiece of fantasy film. His fascination with popular culture, with the feuilleton soap-operas and silent film serials, is clearly visible in movies like Pleins feux sur l’assassin (1960), Judex (1963) and Nuits rouges (1974), true exercises in style striving to recover the innocence of those old narrations of intrigue and mystery in an obvious vindication of film as visual, narrative pleasure. But Franju was also known for his skilful adaptations of classic literary works on which he unfailingly left his personal stamp: François Mauriac (Thérèse Desqueyroux / Therese, 1962), Émile Zola (La faute de l’Abbé Mouret / The Demise of Father Mouret, 1970), Joseph Conrad (La Ligne d’ombre, 1973) and Jean Cocteau (Thomas l’imposteur / Thomas the Imposter, 1964). Today unjustly forgotten, Franju’s work enjoyed great critical acclaim in its time and earned him the admiration of the young filmmakers of the nouvelle vague.