“For me documentaries are no more real than fiction and fiction films no more invented than documentaries,” the filmmaker says of his approach, which he consistently developed since graduating from the National Film School of Denmark in the mid-1970s. (TSM)

JON BANG CARLSEN

– Collected Posts on his Works

by Tue Steen Müller and Allan Berg Nielsen

About Jon Bang Carlsen, who had a retrospective in Bucharest early 2013: With a reference to his films shot in Ireland, ”It’s Now or Never” and ”How to Invent Reality” the Romanian organizers presents Bang Carlsen as ”the inventor of reality”. Here is a clip from the text: “This year One World Romania organizes a retrospective dedicated to the Danish documentary filmmaker Jon Bang Carlsen… a legendary director who reinvented documentary film. In his work, Jon Bang Carlsen has always explored the land between fact and fiction. From 1977 onward, mise-en-scene with real characters plays a very important part in his productions, and this method is detailed in his meta-film, ”How to Invent Reality” (1996). His documentaries are often visually and symbolically powerful staged portraits of marginal figures and milieus that involve compelling stories…” His new film “Just the Right Amount of Violence” were shown at DOKLeipzig and idfa 2013. (TSM)

JENNY (1977)

På billedet ser vi familieportrætter af den alvorlige slags fra fotografen dengang. En kvindestemme, ældre, siger på vestjysk: Det er fredag den anden januar 1977, og jeg føler mig sund og rask… Portrætterne fortsætter i overtoninger, en lille pige bliver ung pige, ung kvinde, ung kone. Og stemmen fortsætter sin optegnelse. En mellemting mellem dagbog og tilbageskuende vurdering, testamente: Der er sket meget i min tid… Og den sammenligner den nye usikkerhed. Vi er i det moderne. I et kontrolrum et sted i USA, har kvinden læst, er der altid to til stede. Hvis den ene skulle bryde sammen og ville trykke på knappen, skal den anden kunne gribe ind. Sådan også på Cheminova, vores kemifabrik. Der er der også to, skulle den ene falde i søvn. For mennesket må selv tage ansvar og ikke give Gud skylden for ulykkerne, det selv har skabt grundlaget for.

Vogels saxofon begynder på et tema. Gruszynskis store landskabsbillede oppefra som hos Søndergaard viser os stedet, vi er. Vestjylland. Refleksionen over kemifabrikken nærmere hvor. Det må være Bovbjerg. Kameraet panorerer til vejen.

To små kvindeskikkelser aser på cykler op ad bakken. Så helt tæt på, især det ene ansigt. Nu ved jeg hvem. Stemmens lyd bekræfter: Min kæde er hoppet af, siger hun. De to får cyklen vendt, forsøger at ordne det med kæden. Med dametasken dinglende ved håndleddet påtager hun sig opgaven. Hun er sej, men må opgive, vel på grund af den lukkede kædekasse. Veninden vender cyklen. Stort landskabsbillede med kirken. Nu lav horisont. Saxofontemaet fortsætter, mens billedet viser os gårdspladsen, et blik ud forbi julestjernen og porcelænshesten i vindueskarmen, ud på gårdspladsen, jeg er kommet ind fra. I det samme er musiktemaet forbi. En telefon ringer. En mand ligger og sover på divanen med avis over ansigtet. Han tager telefonen, spiller dilettant som i forsamlingshuset. De snakker om kæden, nej, han skal ikke hente hende. Nej, det behøves ikke. Jeg kan trække hjem. Det er så godt vejr. Han vender sig og sover videre. Åh, tænker jeg. Nu kommer så historien om et leve livet midt i dette landskab i samtale med Gud. Så fremmedartet og så nært alligevel. Guds plads, menneskets plads, egne kræfter. En tilværelse med tingene i orden. Historien begynder her – kan ses igen og igen, som en gentagen række af ens dage. At kæden hopper af, er her ikke en talemåde, men et problem, som klares…

Jon Bang Carlsen: ”Jenny” (1977) 38 min. Senest set på VHS lånt fra Herning Bibliotek. (ABN, FILM #16)

EN FISKER I HANSTHOLM (1977)

Det lykkedes! Der kom en VHS til mit bibliotek, fra et bibliotek i Århus, hvor de har gemt den siden SFC udstationerede en kopi af hele sin samling der, tror jeg. Men båndet har ikke været afspillet længe. Ved første kørsel var der ikke antydning af billedsignal, kun hist og her spor af en lydside. Men, men efterhånden dukkede filmen op. Et par frem- og tilbagespolinger, og den lod sig se. Og den var netop så smuk, som jeg huskede den… nej, smukkere, faktisk. Det sorthvide fotografi og den nordjyske dialog er i den grad selvskrevet til en DVD reprise. Jeg glæder mig.

“En fisker i Hanstholm” er lige så vigtig for dansk historie og dansk sprog som Hans Kirks bog, som Andersen Nexøs bøger, som Jensens og Hansens. Den lægger sig internationalt i konsekvent forlængelse af den neo-realistiske indsats, og så hører den monumentalt til i rækken af Bang Carlsens store danske film, rækken med ”Jenny”, ”Ofelia kommer til byen”, ”Før gæsterne kommer” og ”Livet vil leves”, den sidstnævnte der som det fineste hængsel knytter denne samlede skildring af dansk sind til instruktørens udlængsel og til skildringen af det fremmede sind i rækken af amerikanske, irske og afrikanske film. Jeg vil tro, at ”Purity Beats Everything” vil vise sig som et tilsvarende kunstnerisk omdrejningspunkt i dette filmværk, hvoraf DVD box 1 vistnok skulle være kommet. Dette grundlæggende filmværk hører som det selvfølgeligste til på ethvert stort dansk bibliotek i VHS kopier, efterhånden på DVD.

Jon Bang Carlsen: ”En fisker i Hanstholm” (1977). Fotografi: Dirk Brüel, klip: Anders Refn. Lene Vasegaard spiller fiskerens hustru, ellers er de medvirkende fra Hanstholm. DFI distribuerer filmen på 35 mm. Set som VHS kopi, Randers Bibliotek, fjernlån. (ABN, blogindlæg 14-05-2008)

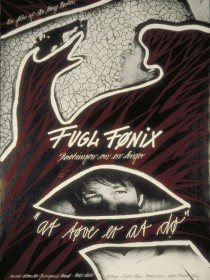

FUGL FØNIX (1984)

Han er vågen før daggry. Han sidder fuldt påklædt i sengen og øver sig i at snuppe pistolen, som ligger på natbordet, for med den og blikket i en lynhurtig bue afsøge rummet. “Freeze”, råber han. Gang på gang. Han øver sig, han er klar, tiden skal gå, for han er klar til at komme i gang. “Kommer den sol aldrig op?” siger han til hunden. Næste billede, solen står op, det er meget smukt, og lyset rammer ham i en stribe over ansigtet. Han ved det, han har ventet på det. Fotografen Alexander Gruszinski har ventet på det. Nu laver de to billeder af den lange række insisterende scener, denne film består. Tydelige billeder af det fremmede, som skal skildres, det anderledes, som set-designet så indlysende rigtigt, uden vi egentlig ved det, tegner som denne anderledeshed.

Han hedder James Jarrett og hans sted er Phoenix, Arizona, og jeg ser så tydeligt, at i Jon Bang Carlsens historie om ham fra 1984 holder i hvert fald fotografiet og set-designet. Anders Refns klip holder bestemt også. Men jeg tøver, interesserer han mig? Interesserer historien mig? 24 år er lang tid. Det er let for mig at rumme Jenny og Bent . Bondekonen og fiskeren. Bovbjerg og Hanstholm. Men dette fremmede, som er tilsvarende fortidigt… men, men meget længere væk?

Jon Bang Carlsen: ”Fugl Fønix” (1984). 49 min. Fotografi: Alexander Gruszynski, klip: Anders Refn. Senest set på VHS fra Herning Centralbibliotek. Kan ses på Filmstriben. (ABN, blogindlæg 17-05-2008)

OFELIA KOMMER TIL BYEN (1985)

Der er langt tilbage til 1985, men det er rejsen værd. På fotografierne fra dengang ser jeg, at Stine Bierlich fik en Bodil (ser det ud til, hun står med den i hånden i en festkjole, som godt kunne være fra filmen) for sin fremstilling af Molly som Ofelia (eller omvendt) i Jon Bang Carlsens modige og fuldstændigt gennemførte film. “En smuk, alvorlig, sjov og skøn film…” skrev Politiken, “..sjælden og fængslende, høj og fin humor.” “En sand glæde” fortsatte Weekendavisen. Og Vestkysten lagde til: “Et folkeligt mesterværk.”

Ofelia har jo en stor rolle, men i kort tid, i Shakespeares stykke. Hos Bang Carlsen er hun det konstant levende, vibrerende og ærlige centrum. Hele tiden øver hun sig på vandets dybder, back stage, var kun hun alene om filmen, ville hun være filmen værd. Blot at følge hendes nuancer i menneskelig følsomhed er oplevelsen. Hamlet/John følger hende i en forceret smuk udvikling mod emotionel ligeværd – Refn klipper det uden rysten på plads. Og når de to trodser skolelærerdilettantinstruktør Ægidius og hvisker Shakespeares dialog til hinanden, laver Bang Carlsen nutidig Hamlet på film, så man bliver tør i munden. Det er SÅ smukt. Dansk film har sandelig en fortid, som kan noget. Må den bare bevares. For eksempel på bibliotekerne. Som den litterære vist nok bliver det. Shakespeare står i kælderen på yderste hylde. På min bys bibliotek

Jon Bang Carlsen: “Ofelia kommer til byen” (1985). Fotografi: Alexander Gruszynski. Klip: Anders Refn. Distribution: www.on-air-video.dk VHS kopi set på www.bibliotek.dk og lånt på Randers Bibliotek, som heldigvis ikke har smidt den ud, men gemt den blandt “ungdomsfilm”, ja, den Shakespeare… Litt.: McGuffin 55/56 http://www.macguffin.dk/texts/Lyset_fra_fyret.htm

(ABN, blogindlæg 09-04-2008)

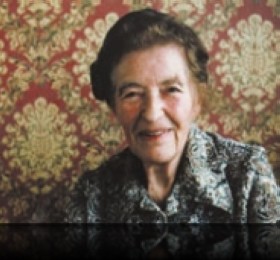

FØR GÆSTERNE KOMMER (1986)

Det var pokkers! Et af dansk dokumentarfilms absolutte mesterstykker bliver genudsendt i morgen tirsdag på DR2. Det drejer sig om Jon Bang Carlsens “Før gæsterne kommer”, en film som med succes er gået verden over for sin fine og varme og sjove beskrivelse af de to gamle damer, der gør et lille pensionat på Fanø klar til det store rykind, det vil sige det beherskede antal først og fremmest tyskere, der år efter år finder vej til den stille idyl.

Værelserne støves af, lamperne checkes, alt skal bringes i orden, det er dansk hygge i yderste potens, som den kunne folde sig ud for 20 år siden – eller rettere sagt som den fremragende dokumentarist Jon Bang Carlsen så den og beskrev den ved hjælp af sin såkaldte “iscenesatte dokumentariske” metode.

En kort film med et langt liv. Vi kipper med flaget for DR2 og deres temaaftener, bliv ved, der er masser af guld at tage af. (TSM, blogindlæg 26-11-2007)

JEG VILLE FØRST FINDE SANDHEDEN (1987)

For mig gik det først galt i den allersidste rekonstruktion. Vel i det 27. minut i dette halvtimes mesterværk om at være klog og 92 og alle de andre er døde og det er altså lidt kedeligt. Men så er der pindsvinet og sommeren og Mozart og kærligheden og bygningerne, som man har konstrueret og kan fare vild i som han gør i sit Lloyds i London.

Til det gik galt, var det nok min yndlingsfilm. Og pyt, det var blot en rekonstruktion, som kiksede. Men til da en fuldendt smukt indfattet perle. Jeg må engang for mig selv prøve at forklare hvordan… Det har at gøre med den vidunderlige medvirkende Erik Arup, som nu længe har været væk. Denne over, over ingeniør. Selvfølelsen selv og beskedenheden selv i én person.

Jon Bang Carlsen: “Jeg ville først finde sandheden” (1987), 29 min. Fotografi: Dan Laustsen. Set på VHS, Randers Bibliotek, fjernlån fra Herning Centralbibliotek. Hvor er det godt, de har gemt den!! (ABN, blogindlæg 15-05-2008)

TIME OUT (1988)

Jon Bang Carlsen castede selv Patricia Arquette i Los Angeles. Det fortæller han i sin bog ”Locations”, valgte hende blandt en mængde helt unge skuespillere, alle dygtige og velforberedte. “Patricias rolle var svær, men jeg synes hun er strålende i filmen”, skriver han i 2002.

Og jeg må sige, han har ret. Filmen kan stadigvæk ses for hendes skyld. I bogen bringer Bang Carlsen to meget smukke billeder fra filmen (side 81 især, og side 81). De indeholder begge Gruszinskis og Bang Carlsens fælles fotografiske magi, som her i “Time Out” også alene gør filmen værd at se igen.

Det gælder derimod ikke Allan Olsen i hovedrollen. Og vanskeligheden ved gensynet er i meget høj grad at se væk fra hans tilstedeværelse. Og det destruerer selvfølgelig historien. Bang Carlsen ved det godt: “Selv om jeg var medproducent bøjede jeg mig for pres fra en anden medproducent og castede ikke den hovedperson, som jeg selv troede på. Det var alene mit ansvar, og både synd for skuespilleren og filmen, at jeg ikke stod fast.”

Så historien er gået i stykker, faldet ud, filmen kan ikke genses som drama, kun som fængslende billedværk (Gruszinski og Bang Carlsen), som en smuk og gådefuld karakterudvikling (Arquette) og som en vigtig brik i den samlede filmrække til nu. Og jeg synes i og for sig, det er meget – og altså i høj grad gensyn værd. En videre opgave er at undersøge filmens sammenhæng med ”Carmen og Babyface” og med ”Ofelia kommer til byen”. Jon Bang Carlsens kvindeskildringer vokser sig i disse gensyn til en vigtig historie helt for sig selv.

Jon Bang Carlsen: ”Time Out”, 1988, 94 min. Kamera: Alexander Gruszinski, medvirkende: Allan Olsen og Patricia Arquette, producer: Gerd Roos, producent: Obel Film. Set på DVD, købt hos Filmkæden http://www.filmkaeden.dk/show.asp?id=2146705112 Litt.: Jon Bang Carlsen: ”Locations” (2002) (ABN, Blogindlæg 24-05-2008)

BABY DOLL (1988)

På DOK2008 forleden bebudede Morten Udsen, efter han havde fortalt om dvd’ernes dramatiske skæbne og mulige fremtid, at der ville komme en box med fire eller var det fem Jon Bang Carlsen film. I forbindelse med premieren på “Purity Beats Everything” 23. april i filmhuset vistnok… Til salg i boghandlen i huset vistnok… I hvert fald et godt valg. Art People står for distributionen http://www.artpeople.dk/ Men der er god grund til at fortsætte eftersøgningen af instruktørens tidlige film, lige nu opleve værkets fulde udstrækning, for utålmodige jeg ved godt, at det kan have lange udsigter med finansieringen af den planlagte fortsættelse, hele Jon Bang Carlsens værk på dvd-boxe. Og jeg er i hvert fald bange for, at det ikke lykkes at få spillefilmene med.

I 1988 blev “Ofelia kommer til byen” efterfulgt af “Baby Doll”, hvor alt samles i et kammerspil, i køkkenet mest, på en vestjysk gård. En kvinde alene med sit nyfødte barn møder helt alene de dæmoniske kræfter, vi rummer i vores fortrængte erindring, og overgiver sig lettet efter sej kamp til dem og går som Ofelia ud i vandet. Mette Munk Plum gennemfører alene, stort set, denne timelange tour de force. Grethe Møldrup har roligt klippet thriller-kurven i smukke afsluttede scener, som man ikke kan ryste af… Munk Plum spiller dem igennem lyrisk, men med dramatiske udbrud, med kortere og kortere intervaller fornemmes det, udbrud af vrede først, derefter apati, så angst og endelig overgivelse og hengivelse. En kurve som Deneuves i Polanskis “Repulsion”, men genkendelig og således farligere.

For i modsætning til Alexander Gruszynskis mytologiske Bovbjerg, som Ofelia og hendes Hamlet færdes i, har Björn Blixt fotograferet moderen Eva og hendes barn i et dokumentarisk skildret landskab, klitten og stranden er lys lys, og i interiører, som er nøgternt præcise billeder i en scenografi, der som kunstgreb har gjort sig usynlig i en genkendelig realisme. Dørkarmenes farve, gulvenes fernis, hændernes og de nøgne fødders berøringer så taktilt virkelige…

Og alt er også genkendelige Jon Bang Carlsen billeder. Portrætterne på væggen, penduluret, tørresnoren, et blåt klæde, som pludselig dækker scenen af. Og ude gårdsplads og indgang og trappesten som disse huskes. Grusvejens slyng i landskabet. Både Mols og Vestjylland. Det lange filmværks sammenhæng.

Jeg har kun en enkelt indvending, til en detalje i lyddesignet, en bestemt overdrivelse, som rammer min ideosynkrasi, men det er fuldstændig lige meget nu efter de mange år. Alt det vigtige er så lykkeligt bevaret.

Jon Bang Carlsen: “Baby Doll” (1988) Crone Film Produktion. DVD: www.on-air-video.dk Lånt på Randers Bibliotek, fjernlån. (ABN, blogindlæg 19-04-2008)

LIVET VIL LEVES (1993)

Denne maj måned bringer Dox On Wheels Jon Bang Carlsens nye film “Purety Beats Everything” til en række byer til biografvisninger, hvor han selv er der, nogle gange i samtale med en åndsbeslægtet. Det erindringsbaserede filmværk bringes håndfast i forbindelse med den konkrete auteur, biografisk og moralsk. Og en del nyfigent som det er så VIGTIGT nu.

Mens jeg venter, gennemser jeg, hvad jeg kan få fat i på mit bibliotek, og det viser sig, at det som fjernlån fra Herning Centralbibliotek er muligt at låne en VHS af “Livet vil leves” fra 1993.

En mor skriver breve til sin voksne søn, som er på rejse i USA. Sønnen skriver sine refleksioner, i dagbogen vel. De to tekster læses på lydsiden af to skuespillere. Billedsiden er dels landskabsoptagelser fra rejsen på prærien og i ørkenen, dels landskabsoptagelser fra Bovbjergegnen, hjemegnen siges det. Axel Schiøtz synger en arie fra Messias. Det er det.

Og det bliver til en åndeløst dybt åndende film på næsten 50 minutter. Som jeg – indser jeg nu – i detaljer husker fra premieren for 15 år siden. En film, som ikke har rokket sig det mindste siden. Den er så ny og inderligt vedkommende som dengang.

Jon Bang Carlsen: “Livet vil leves” (1993). Mesterligt fotograferet af Alexander Gruszynski, Mikael Salomon og Henrik Jungdahl. Vidunderligt kongenialt klippet af Grethe Møldrup. DFI har kun en 35 mm kopi, men bibliotekerne (i hvert fald Herning Centralbibliotek) har heldigvis gemt VHS kopier. (ABN, blogindlæg 27-08-2002)

CARMEN OG BABYFACE (1995)

De har gemt en VHS kopi på mit bibliotek. Hvor godt, for gad vide, om de kunne finde på at købe en DVD? Og der er nok lang tid til, den kommer som en del af Jon Bang Carlsens DVDBOX. Båndet kørte imidlertid fint, jeg kunne godt se, at Dan Laustsens billeder er meget, meget smukke og meget Bang Carlsen tro. Og Grethe Møldrups sindrige, betydningsladede og meget enkle klip bar mig igennem den helt enfoldige og dybt rørende historie i et gensyn så forbavsende, som var årene slet ikke gået. Årene siden midt i 90’erne, da filmen var ny, årene siden først i 60’erne, som er fortællingens tid. Filmens liv, mit liv erindret fra i aftes. Hvor alt jeg så, var autentisk og friskt og originalt og fuldstændig logisk på plads i Jon Bang Carlsens samlede værk. Mere personlig og modigere måske, end nogen af hans øvrige film, tror jeg, nu efterhånden. Som jeg ruller denne lange gensynsserie ud.

Vi er i 1962. I kunstnerhjemmet, to keramikere på vej fra hinanden og deres to voksne børn. Vedbæk først, det så dejligt ombyggede udhus, hvor de endnu er sammen. Så landsbyhuset i Kønsløse, hvor moderen og børnene bygger det fraskilte liv op. Og i hvert fald to af dem forelsker sig… moderen igen, sønnen for første gang. I hans første kys slutter fortællingen, men lever videre i dem og i os, som vi senere vil lære i “Blinde engle”, at fortællinger gør.

Det er i kernen den evige fortælling om kvindens drøm om mandens styrke. Mandens drøm om kvindens mod. Den blide mand og den voldsomme kvinde. Den modige mand og den stærke kvinde.

Jon Bang Carlsen: “Carmen og Babyface” (1995). Kamera: Dan Laustsen, klip: Grethe Møldrup, produktion: Peter Aalbæk Jensen for Zentropa, Nordisk Film og Carlsen & Co. Medvirkende: Rasmus Seebach, Sofie Gråbøl og Ulla Henningsen. Set på VHS fra Randers Bibliotek. (ABN, blogindlæg 23-05-2008)

IT’S NOW OR NEVER OG HOW TO INVENT REALITY (1996)

Når Jon Bang Carlsen i It’s Now or Never lader de medvirkende i Vestirland spille løs, ikke deres egne liv, men digtede liv, ikke i deres egne huse, men i huse, han har fundet velegnede til den særlige stemning, han ønsker i sin film, kunne man hævde, det ikke længere er dokumentarfilm, han laver, men fiktion. Men egentlig er det lige meget, blot det er en enestående oplevelse. For så er alle midler tilladte, skrev juryen i sin begrundelse for at give ham grand prix på Dansk Film Festival i Odense (1996). ”Vi behøver ikke at klassificere et sådant værk som det ene eller det andet. Det er bare en glæde at tage imod med åbent sind”. Som Christian Braad Thomsen fortæller om Karen Blixen i sin film om hende: ”Hun digtede frejdigt om på sandheden for skabe sand digtning.”

Og Bang Carlsen har villet lave et sandt filmdigt om en fattig tilværelse omgivet af stor skønhed på den barske Atlanterhavskyst. Hovedpersonen Jimmy køber en ny ko. Den kan tydeligt ikke lide ham (eller filmholdet?) og vil kun nødtvunget ind i hans gård. Og sådan går det formodentlig også, da han omsider gennem en ægteskabsmægler får kontakt med en kvinde at gifte sig med. Filmen slutter netop som kontakten er etableret. Jimmy har stillet samme nøgterne krav til konen som til koen. Hun skal kunne malke, den give mælk.

Det er godt, at Bang Carlsen lavede How to Invent reality også, mens han var i Irland. Den samme historie for så vidt, men set fra kulissen med alle snorene, billedernes bagsider og skkuespillernes ventetider, så deres persona demaskeres. Og vi ser hvor tynd masken er, hvor vellignende.

Formen er jo set før, et dokumentarhold følger filmoptagelserne og portrætterer instruktøren. Her bliver det noget mere, meget mere. Bang Carlsen udvider værket med et selvportræt, fortæller løs om, hvad det var, han ville, hvordan han gjorde, og hvordan han syntes, det gik. Praktisk og i rask tempo. Det bliver til en hverdagstekst fuld af arbejdsdagens rigdom og filmisk teori. Og humor. En vældig tekst er den film, om det at lave et billede, et kunstværk.

Mange siger, at How to Invent Reality er en bedre film end It’s Now or Never. Jeg slutter mig til. Jeg ser også problemerne i It’s Now or Never. Synes, at filmen har opbrugt sin energi langt før slutningen, mener at hovedpersonen slet ikke er stærk og interessant nok til at bære så mange gentagne ture. Han synger titelmelodien mindst én gang for meget. Og jeg synes også, at den meget mindre villende journalfilm, som registrerer og diskuterer kunstværkets tilblivelse, har den charme, hvormed skitsen i gamle dage overgik udstillingsbilledet i intensitet. Men det er også sådan, at dette filmessay var meningsløst uden dokumentarfilmen, det diskuterer. Tilsammen er de film et forunderligt værk om nogle kantede mænd, som forsøger at nærme sig det eksistentielle og det poetiske. De er så forsigtige med deres grove hænder og ekstremt gearede motorik, at de nok ikke når at røre ved den kærlighedsfølelse, projektet gælder. Vi får næppe øje på følelsens fossil i deres bjerge af kroppe. Til gengæld bliver følelsen heller ikke kvalt i udpensling. Den er stadig den lyslevende længsel.

Danmark 1996, 45 min og 31 min.

SYNOPSIS

”It’s Now or Never”. The Irish West Coast, both harsh and beautiful, creates the frame for this humoristic documentary. The main character is Jimmy, middle aged and lonely. Of earthly creatures seen from his window is an equally lonely cow which has been bought by Jimmy from his bachelor friend, Austin. Jimmy would like a woman to share his life and looks up a matchmaker who dutifully asks him about his wishes and preferences. Jimmy bides his time, fantasizes, chats with the boys, asks God for advice and builds stone dikes, all the while humming that ‘it’s now or never’. Then, this rugged man gets a telephone call from the matchmaker. (dfi.dk/faktaomfilm)

”How to Invent Reality”. A demonstration of Jon Bang Carlsen’s method using the example of his film about Irish bachelors, “It’s Now or Never”. At one point in this essay about documentary staging someone says: “You move into a film like you move into a house.” Whether you feel comfortable there, however, depends on many small, sometimes unnoticeable things. That’s what Bang Carlsen talks about in this film: the search for protagonists, places, events, moods, and their translation into a cinematic narrative. That’s why what we finally encounter in the cinema is neither the protagonist’s story nor the director’s. Instead, the film has found its own truth. And that’s the wonderful thing about filmmaking. In that sense you can’t help agreeing to another comment by Bang Carlsen about his documentary method: “It’s a result of mistaken orthodoxy to be limited by the way the world happens to look.” (Matthias Heeder, Dok-Leipzig) (ABN, blogindlæg 20-05-2015)

It’s Now or Never: Filmcentralen / For alle streaming

How to invent Reality: filmcentralen.dk/alle/

Om filmen: dfi.dk/faktaomfilm

Jon Bang Carlsen om sit værk: FILM-Magazine

Litt.: Lars Movin: Jeg ville først finde sandheden, 2012, 372ff (Hovedværket om instruktøren og om disse film)

PORTRÆT AF GUD (2001)

Hvor er dette sted frygtindgydende! Det er jo selve Guds hus, det er himlens port! (1. Mosebog, 28. kapitel, 17. vers)

Da Albrecht Dürer for femhundrede år siden skulle male sit portræt af Gud, af Jesus fra Nasareth, valgte han at kombinere det med sit spejlbillede, så det på Pinakoteket i München og i den meste litteratur benævnes selvportræt. Og jeg glider da også, mens jeg betragter det, hele tiden fra at se fremstillingen af malerens indsigt i det sjælelige i sig selv til hans skildring af det guddommelige hos denne allerede dengang forsvundne – som Jon Bang Carlsen i sin film leder efter på beslægtet måde.

Da Rembrandt hundrede og halvtreds år senere med syre, gravstikke og koldnål bearbejdede kobberpladen, som skulle trykke raderingen Kristus Prædiker valgte han at flytte fokus fra portrættets psykologi til dokumentarismens antropologi. I et spottet lys oppefra står Jesus stilfærdigt med lidt sænket hoved og med hænderne hævet i en gestus. Han står på en lav stentrappes repos og taler til en gruppe mennesker forsamlet i en baggård. Jesus er blandt fattige. Almindelige folk. I Amsterdams jødiske kvarter havde Rembrandt studeret det anderledes folkeliv og i raderingen her blev de mange skitser samlet i ét udtryk. De forskellige fysiognomier, alle markante, møder med omhyggeligt varierede ansigtsudtryk prædikantens ord.Scenen findes tilsvarende i Jon Bang Carlsens film. Dette dokumentariske greb, i det lyttende ansigt at spore en tanke, som ikke har nået sit sprog. Som måske har karakter af den tvivl, som så overraskende viser sig som en facet af troen.

Da Lauritz Jensen fra Essenbæk i Jylland en menneskealder senere end Rembrandt skulle skære billederne i en ny syddør til en stor bykirke i nærheden af landsbyen, hvor han boede, valgte han fromt og rettroende at gå til bibelteksten, før han fremstillede Jakobs Drøm i dørens topfelt. Omhyggeligt forevigede han skriftstedets bogstaver: Hvor forskrækkelig er denne sted, her er ikke andet end Guds hus og himmelens port, patriarkens udbrud, da han vågnede efter søvnen, hvor han havde set stigen ind i himlen. Og øverst over englene op og ned – Gud selv. Hvordan så han ud? Jensen vidste det godt. I hans egen kirke ude i Essenbæk var der en gammel skulptur fra et sidealter fra den katolske tid. Gud Fader som den gamle af dage, denne strenge, gamle mand, som profeten havde skildret ham med kongekåbe og uldskæg. Sådan blev så også Jensens portræt af Gud 1688. Sig ikke det billede siden er forsvundet fra vores bevidsthed.

Træansigtet på døren. Stenansigtet i havet. Jon Bang Carlsens film. Instruktøren føjer sig til rækken af malere og billedskærere, som har skildret Gud og troen. Han er både den fromme og naive Jensen, den dokumentariske og ærlige Rembrandt og den selvbevidste og modige Dürer. Hans film er noget så gammeldags som en moderne, humanistisk trosbekendelse. Men sært reaktionært sættes den op i en dynamisk og udviklet nyromantik, så den bliver en meget nutidig katekismus med tidssvarende spørgsmål og svar.

Instruktøren udspørger den medvirkende præst og er i sin troslære kommet til tvivlens plads:

Præsten: Det modsatte af tro er ikke tvivl. Det modsatte af tro er vished.

Bang Carlsen: Det var en god formulering. Kan du gentage den?

Præsten: Ja. Det modsatte af tro er ikke tvivl. Det modsatte af tro er vished. Hvis jeg følte mig sikker på Gud, ville jeg opgive min tro helt.

Bang Carlsen: Indbefatter Gud… Besidder han… Tvivler han selv?

Præsten: Det er en interessant tanke. Det tror jeg aldrig jeg har tænkt på. Jeg er sikker på – at tvivlen på en eller anden måde må være en del af Gud… Det er faktisk for omfattende overhovedet at spekulere på. Det må jeg lige overveje…

(’Den gamle af dage’ er også et bibelsk udtryk. Daniel 7,13 og 7,22. ABN, tale ved premieren i Sct. Petri Kirke i København)

PURITY BEATS EVERYTHING (2007)

Miriam Lichterman lives in Cape Town with a view to beach and sea. Jon Bang Carlsen lives in a farmhouse with a fine view to a beautiful landscape in Denmark with family, cat and dogs. She is a holocaust survivor, a Polish Jew, who saw the horrors of Auschwitz from the closest distance, he is a filmmaker born after the war. He grew up in the 1950’es in silence when it came to family talk about holocaust.

She is a brilliant storyteller, and so is he. She – with the words of Jon Bang Carlsen –deals with the cruelties as an artist, the only way for her to overcome it, she talks with a sincerety that brings the past into present time. I have to look her into her eyes, the director says, I can not just stay behind the camera. She has told her story again and again, he has to find a way to bring to life one more holocaust survivor story, told by Lichterman and Pinchas Gutter.

”Nothing is ever gone” could also have been the title of this film that is an indirect, non-bombastic poetically told appeal to think about the past and the present. To give the spectator his point of view, Jon Bang Carlsen has chosen to contrast the story of the survivors with images from his farmhouse idyllic surroundings, interrupted by some archive from the horrors – and with a sound score that introduces among other speeches by Hitler, Rimsky-Korsakov ”Sheherazade”, weather sounds from the Danish farmhouse, a phone that brutally cuts the directors computer-viewing of his material, and last but not least his own voice with clever reflections on the theme of purity and cleansing.

It is a montage with many layers and with some of the usual magnificent images that you only find by this unique Danish filmmaker, who never stops to challenge himself. Image: A shirt on a clothesline blowing violently in the wind. Sound: the screaming insane voice of Hitler to be overtaken by ”Sheherazade”. Or the marching soldiers of Hitler on the sound track accompanied by pegs on the clothesline moved again by the wind. I could go on, check for yourself this FILMmaker, and meet him on his tour around Denmark or invite him to your festival or film meeting. Or buy his film for television. Danish readers have the chance to read about Carlsen’s previous films, written on this blog by colleague Allan Berg.

Denmark, 2007, 52 mins. (TSM, Blogpost 21-05-2008)

TRILOGI + 1 (2008)

DVD-boksen indeholder fire film, den sydafrikanske trilogi, ”Addicted to Solitude”, 1999, ”Portrait of God”, 2001, ”Blinded Angels”, 2007 og så ”Purity Beats Everything”, 2007. Og jeg tager filmene op her, fordi de, og især den seneste film, bliver emne for næste aften i min filmklub. Vi er godt forberedt, vi har Tue Steen Müllers vidende og anerkendende anmeldelse her på filmkommentaren (se ovenfor), nogle har set filmene i forvejen, den seneste har været i biografen de senere måneder i en række byer, og instruktøren har været til stede, og den har været vist på DR2 på den sene kvalitetssending.

Men der står for mig stadigvæk en række spørgsmål tilbage at overveje, i første omgang om forbindelserne mellem de tre plus én film, og om, hvordan denne trilogi-konstruktion hænger sammen med den sidste titel, som sådan er løst tilknyttet. Og jeg må prøve at finde ud af, hvordan de fire film griber tilbage i det tidligere værk, måske helt tilbage til “Jenny” (1977). For alt i dette filmarbejde over fire årtier væver sig for mig at se sammen i nye betydninger.

De medvirkende i ”Purity Beats Everything”, Miriam Lichterman og Pinchas Gutter fortæller deres erindringer fra Auschwitz. Det vidste jeg på forhånd var det forfærdende indhold, men som Tue Steen Müller gør opmærksom på, peger filmens fortæller også på, at denne erindring for længst blevet til fortælling, til en kunstnerisk bearbejdelse. Og filmen fortsætter i det spor, bygger yderligt i en række lag på beretningerne, først den frapperende del af billedsiden med optagelser fra en sjællandsk gård, og jeg ser, at grebene oven i de idylliske landskaber, som rigtignok tilvejebringer en udholdelig kontrast, eller i hvert fald anderledeshed, er talrige og fyldt med foruroligende tankebearbejdelser af de medvirkendes erindringer.

De mange velkendte træk fra de tidligere film: lyden fra optagelserne i arbejdsværelsets computer (”Portrait of God”), den velkendte håndskrift på skiltene (“Livet vil leves, breve fra en mor” og mange gange siden), hver eneste beskæring, belysning og motivvalg i hvert eneste billede (“Før gæsterne kommer” ja, og “Jenny” og konstant siden). De mange velkendte træks tryghed gør, at jeg overhovedet kan lytte til de ufattelige detaljer og tage dem ind, men stadig uden at fatte dem. Forstå, ja det er umuligt. Der tager filmen fat på det afgørende lag i konstruktionen. Det har med de hjemlige ting at gøre. Derfor denne vedholdende skildring af kunstnerhjemmet, hvor filmen er blevet til, hjemmet med vasketøjet og tørresnoren.

Det hjem kender jeg også i forvejen. Fra flere steder, tydeligst fra ”Carmen og Babyface”. Hvad det så betyder, vil jeg tænke videre over og snakke med dem om i filmklubben. Men her skal lige noteres, at med denne DVD-boks er endnu et umisteligt filmværk bevaret til et nyt liv i dette filmformat for alle hjemmene. Måtte de øvrige film snart følge efter.

Jon Bang Carlsen: ”My African trilogy plus one”, 2008. C&C Production, distribution: Danish Filminstitute bookshop@dfi.dk (ABN, blogindlæg 14-10-2008)

ADDICTED TO SOLITUDE (1999, i boksen ”My African trilogi plus one”, 2008)

Det er et privilegium at åbne en DVD boks som denne. Så smuk den er, personlige grafiske løsninger.. indeni den nye film, som vi har skrevet om og så de tre ældre., alle mere personlige film end ellers.. også mere personlige end jeg husker dem.

Hvad vil nu det sige? Jo, instruktøren er til stede i det hele, fra yderst til meget langt ind, til lige netop der, hvor de medvirkende tager over. Hans malererfaring og hans håndskrift møder jeg på boksen og indeni på kassetterne på DVD omslagene, og med det samme i teksterne, som ikke er tekstforfatterens, men hans.

Jon Bang Carlsen omgiver sine film med ord, også denne, så værket består af en film og en mængde forklaringer, kommentarer og refleksioner, som ude i virkeligheden fortsætter i interviews, artikler og bøger. Så jeg må se alt og læse alt, hvis jeg vil gøre mit publikumarbejde færdigt. Men hurtigt flytter ordene ind i billederne, teksten ind i scenerne, butikken og kirkegården, farmen og landskabet. Og bliver de medvirkendes ord tillige. Og filmen vokser ud af skitsen, den begyndte med, til mesterværket, den er.

Jon Bang Carlsen: ”My African trilogy plus one” (2008) (ABN, blogindlæg 27-10-2008)

BUCHAREST 2013

Danish master Jon Bang Carlsen is in Bucharest these days. He has been invited to present a retrospective of his works at the International Human Rights Documentary Film Festival, One World Romania, that runs until March 17, like the one in Prague, ”in memory of Vaclav Havel”. With a reference to his films shot in Ireland, ”It’s Now or Never” and ”How to Invent Reality” the Romanian organizers presents Bang Carlsen as ”the inventor of Reality”. Here is a clip from the text:

“This year One World Romania organizes a retrospective dedicated to the Danish documentary filmmaker Jon Bang Carlsen. Fairly unknown in Romania, but considered a legendary director who reinvented documentary film, Carlsen will be… a special guest of the festival. Between the 11th and the 17th of March, the audience will have the chance to see more than half of his works, produced between the 1970s and 2013, and to participate in debates with the director.

In his work, Jon Bang Carlsen has always explored the land between fact and fiction. From 1977 onward, mise-en-scene with real characters plays a very important part in his productions, and this method is detailed in his meta-film, ‘How to Invent Reality’ (1996) – which will also be screened in Bucharest. His documentaries are often visually and symbolically powerful staged portraits of marginal figures and milieus that involve compelling stories…”

There are many other films at the festival, ”Shoah” in its full duration and ”Act of Killing” just to mention two masterpieces.

http://oneworld.ro/2013/l/en/news/103/jon-bang-carlsen-at-owr-the-inventor-of-reality-in-bucharest/ (TSM, blogpost 13-03-2013)

LARS MOVIN: JEG VILLE FØRST FINDE SANDHEDEN (2013)

.. med undertitlen ”Rejser med Jon Bang Carlsen”. Læserne af denne tekst skal til start vide, at såvel Jon Bang Carlsen som Lars Movin i årtier/årevis har haft en høj stjerne hos undertegnede blogger. Jeg har i de 20 år, jeg var ansat i Statens Filmcentral skrevet og talt om Jon, jeg har givet grønt lys til de mange filmpjecer og –plakater, som blev lavet til hans film og jeg har indstillet flere af hans film til økonomisk støtte. Jeg har rejst med Jon til festivaler og vist hans film på filmskoler og seminarer. Alt sammen med glæde. For Jon er sin generations vigtigste dokumentarist og har et velfortjent solidt internationalt ry.

Når det kommer til Lars Movin, har jeg altid betragtet ham som en fremragende kulturjournalist, som fornemt i og udenfor dagbladet Informations spalter er fulgt i Erik Thygesens fodspor med sin enorme viden om amerikansk underground. Han har skrevet om beatgenerationens kunstnere, han har nedfældet sine rejseindtryk – og han har været den danske filmkritiker og – skribent, som bedst har fulgt og beskrevet den nyere danske dokumentarfilm. Og han har selv lavet film. Hvilken energi og flid, har jeg tit tænkt om Lars Movin.

Og nu har de to rejst sammen til de steder, hvor Jons film er optaget for gennem samtaler at komme tættere på instruktørens måde at arbejde på og finde ud af sammenhængen mellem ”liv og værk, mellem biografi og fortælling”, som Lars formulerer det i sit forord.

Resultatet er blændende, den bedste filmbog jeg har læst i årevis – og lad den bibliotekaruddannede blogger med det samme også rose bogen som bog: 560 sider, velillustreret, med et detaljeret noteapparat, et navneregister og en kommenteret filmografi. Det er et imponerende arbejde, som her lægges frem af Lars Movin og bogen kan læses fra start til slut, eller man kan hoppe rundt i den og bruge den som opslagsværk.

”Rejsen til Amerika” hedder det første kapitel og her er de to på hjemmebane. Det bliver til afsnit om mesterværkerne ”En rig mand” og ”Hotel of the Stars”, om spillefilmen ”Time Out”, der blev et nederlag for instruktøren med en af flere fejlcastings, som han efter eget udsagn har lavet i sin karriere. Samtidig taler de to om ”Just the Right Amount of Violence”, filmen som endnu ikke har haft dansk eller international premiere. Jon Bang Carlsen formulerer sig igen og igen, så man har lyst til at citere ham, og det er Movins fortjeneste at sætte de mange sprogblomster ind på de rette steder og trække tråde fra det ene udsagn til det næste.

Men måske er det kapitlet ”Sjælens grundlandskaber”, som er det mest centrale for forståelsen af, hvorfra Jon Bang Carlsens stof stammer. Det tætte og komplicerede forhold til moren, som han voksede op hos, skilsmissen, hendes selvmordsforsøg og det uafklarede forhold til faren. Familierne Bang og Carlsen og deres tilhørsforhold, Kyndeløse – ”i erindringen et mentalt landskab for Cubakrise, postskilsmisse og teenage-spleen”, som en billedtekst lyder (side 150). ”Livet vil leves – breve fra en mor” er vel den film, der kommer tættest på moren, jeg husker, hvor forbavsede vi blev i Statens Filmcentral, da morens breve blev læst af Bodil Kjer. Denne gang en perfekt casting!

Og så kapitlerne om de ”danske” film, ”Jenny” først og fremmest, men også ”En fisker i Hanstholm”, hvor tilblivelseshistorien i bogen giver bevis for Jons herlige evne for den sproglige anekdote. Jo, humor er der i bogen – og i ”How to Invent Reality” fra den irske periode, som i øvrigt er lidt tyndt beskrevet i forhold til de andre rejser, inklusiv sidste kapitel, hvor de to rejsende er i Sydafrika, som instruktøren har opholdt sig i gennem mange år og lavet mesterlige film som ”Addicted to Solitude”. Her finder de hovedpersonen fra denne film, Brenda, som i 1999 ikke vidste, hvor hendes mand var blevet af og i 2012 er blevet gift og har børn. I de sydafrikanske afsnit folder Lars Movin sig ud som den nøjagtigt observerende, smukt formulerende rejseforfatter, han er.

Jeg har ikke skrevet meget om Jon Bang Carlsens metode, den iscenesatte dokumentarisme, som det rejsende makkerpar vender tilbage til igen og igen. Det er godt formidlet, hvordan metoden er anvendt, hvordan instruktøren hele tiden prøver noget nyt og udfordrer sig selv: ”For mig handler det om at nulstille sig selv hver gang, man skal starte på et nyt projekt, og så pejle sig ind på, hvilken form der vil være brugbar denne gang” (side 188).

Der er masser af stof at blive klog på for den, der vil vide mere om at lave film og vil møde en instruktør, der har været ærligt tvivlende overfor hver ny opgave, har været (og er) stærkt produktiv, en visuel begavelse, et menneske der med en genert kejtethed altid har været i stand til at komme tæt på sine personer, der på den ene eller anden måde har indeholdt noget af ham selv. Men bogen kan også læses som en selvbiografisk rejsebog af den, der ikke er specielt interesseret i iscenesat dokumentarisme eller kender nøje til instruktørens værker.

Informations Forlag, 2012. (TSM, blogpost 07-08-2013)

I KÆRLIGHEDENS NAVN (2013)

This is a Danish language review of the new film by Danish director Jon Bang Carlsen, whose work has been written about on filmkommentaren several times. ”Just the Right Amount of Violence” is a multi-layered, personal documentary in the hybrid form that the director has performed for decades long before that genre became à la mode. The film has already been shown at main festivals like Hot Docs in Canada, DOKLeipzig and idfa, Amsterdam. Today it has its premiere in Danish cinemas.

En enestående film. En mislykket film. Enestående fordi Jon Bang Carlsen igen er den han er, en ener i dansk film, med sin helt egen stemme, altid på vej et nyt sted hen i sin konstante udvikling af sine originale visuelle fortolkninger af en verden, som han forsøger at forstå fra sit eget ståsted, med sine egne erfaringer, i dette tilfælde hans smertefyldte forhold til sin far. Mislykket, som han selv siger i filmen, fordi han aldrig får adgang til det genopdragelsescenter i Red Rock Utah USA, hvortil filmens to uvorne unge bliver transporteret efter at være blevet afhentet i deres hjem, midt om natten, på fædrenes bestilling.

Her er den ydre fortælling, som løber filmen igennem: To velvoksne såkaldte ”transportspecialister”, én af dem hedder Bullet (!), bliver lukket ind i pæne forstadshuse og med fædrene som vejvisere ført til de unges soveværelser. De unge (navnene er Simon og Lucy) bliver vækket og ført ud til den bil, som skal føre dem til den institution, hvor deres genopdragelse skal finde sted. Det er dramatiske optrin, som Jon Bang Carlsen har iscenesat, de unge gør modstand både ved ”kidnapningen” og undervejs på rejsen i bilen. De unge skuespillere som instruktøren har valgt, spiller glimrende, specielt Lucy, hvis historie også omfatter arkivmateriale fra hendes barndom. Om det så er autentisk og knytter sig til den historie, som er Lucys, er ligegyldigt, det fungerer i den filmiske sammenhæng. Familiebilleder, home-videos som illustrerer lykke.

De dramatiske episoder afbrydes konstant i den kapitel-opdelte fortælling. Bullet fortæller om sin opvækst (”jeg boede på et toilet som 23-årig”) og om sit kidnapper-job, som han vel egentlig ikke synes om. Han siger på et tidspunkt, at det i de fleste tilfælde er forældrene, det er galt med – og vi ser ham med venner og kolleger spille bold på de solbeskinnede strande nær Los Angeles, steder som Jon Bang Carlsen vender tilbage til, smukke er de, som de ligger der, fredfyldte og samtidig nær Englenes By, ”City of Dreams”. Broken dreams i dette tilfælde. Bang Carlsen føler sig hjemme i disse omgivelser.

Ind imellem de dramatiserede sekvenser og de dokumentariske indslag med Bullet og hans kolleger, er der så et interview med en ung mand, som har været igennem projekt genopdragelse – det er rare sager man hører fra ham – og i et dokumentarisk skype-interview med en far, som sendte sin datter afsted. Hans ansigt ses halvt, hans stemme svarer på Bang Carlsens spørgsmål, inklusiv det penible om farens påståede overgreb på datteren.

Det er et chokerende tema, der gennemspilles: bortførelse med vold, ulykkelige barndomsoplevelser og specielt historien om Lucy er godt gennemført til det øjeblik, hvor man må forestille sig, hvad der sker på den anstalt, som Bang Carlsen ikke kunne komme ind i.

Hovedmotivet i filmen, instruktørens personlige begrundelse for at lave filmen, præsenteres allerede i filmens første sort/hvide familiebillede, hvor en far omfavner sin søn. En far som forlod ham, akkurat som fædrene i filmen svigter, efterladende åbne sår som har svært ved at heles. Alvorligt, men så kan tonen pludselig blive en anden, når instruktøren siger ”fathers run out of battery and lose contact”!

Instruktørens personlige historie bliver berørt billedmæssigt gennem få arkivbilleder, der sættes ind, akkompagneret af instruktørens (engelske) tekst. Igen fylder teksten godt i en Jon Bang Carlsen film, men her virker den balanceret, speaket af ham selv med en ofte sørgmodig stemme. Bang Carlsen er ikke bange for at være patetisk, på nudansk og ganske udansk for nyere danske film ”giver han den hele armen…”

Men der er også glimt af den humor og selvironi, som kendes fra flere af instruktørens tidligere værker, f.eks. i How to Invent Reality, hvor han redegører for sin metode, som han gør her ”I Kærlighedens Navn”, hen mod slutningen, hvor han siger til skuespilleren, der er Martin: “The Worst Thing in Making Films is to Make Focus”.

Og det er helt klart, hvad Jon Bang Carlsen, med sit krøllede hovede fyldt med vidunderlige visuelle påfund og med en fortællestruktur, som går i mange retninger, her har haft det svært med. Hans far havde sikkert ret, når han kaldte ham ”professoren”! Denne anmelder løfter på hatten for de mange fortællelag, mere eller mindre fokuserede er de (jeg ville godt have haft mere selvbiografisk stof, specielt efter at have læst Lars Movins bog om/med instruktøren), og måske kunne man have undværet kapitelinddelingen, som er lidt af en show-stopper, men det er små indvendinger, når man har set en film, som er chokerende i sit amerikanske tema, gribende i sin personlige tekst, en social film fortalt i en essayistisk form. En ener i dansk film er JBC.

Danmark, 80 mins. English title: “Just the Right Amount of Violence” (TSM, blogpost 05-12-2013)

RETROSPEKTIVE IN LEIPZIG 2014

DOKLeipzig 2014 presents an ”homage to Jon Bang Carlsen”. A long text from the festival site follows below. The director is also to make a masterclass at the festival. To be recommended. Masterclasses with Bang Carlsen are always lively and entertaining and fine invitations to enter his world. We two editors of filmkommentaren.dk – Allan Berg and Tue Steen Müller – have followed the work of the director for decades, as film consultants who have supported on behalf of the Danish Film Board and Film Institute, and in writing. Allan Berg has made – primarily in Danish – a ”Jon Bang Carlsen. Collected Posts on His Work” (in Danish and English), it will take you a good amount of time to read about the many films of Bang Carlsen, and you will enjoy it.

A retrospective in 2014 – I attended the first international retrospective of the director in 1988 in Montecatini in Italy, quite an honour it was, the same year as Nagisa Oshima was there with his feature film series. Two years later, in 1990, Jon Bang Carlsen was in Montecatini again, where he with ”Baby Doll” won the ”Airone d’oro”, the golden heron, symbol of the city. I was there on both occasions and remember that Jon asked me in a press release to change the heron into a swan, sounds better he said, as ”hejre” in Danish at that time was a not very nice chauvinistic reference to women.

Back to Leipzig retrospective, here is the text from the site: ”How authentic can a documentary be? Jon Bang Carlsen of Denmark delves into this question in his films. His work is deliberately perched on the boundary between documentary and fiction. DOK Leipzig pays tribute to the master of this mixed form this year with an homage and offers insight into his sensational documentary method.

Bang Carlsen takes the approach that there is no objective reality in the documentary, but that the presence of the camera alone changes the daily life of the protagonists. “For me documentaries are no more real than fiction and fiction films no more invented than documentaries,” the filmmaker says of his approach, which he consistently developed since graduating from the National Film School of Denmark in the mid-1970s.

“Staged documentaries” are what he calls his films, in which he has real people play story lines he conceives. The facts are not crucial for Bang Carlsen, just the story. The Dane takes the lives of his protagonists as a basis and writes a screenplay for them in their own everyday language. The script is based on thorough research of the locations and a study of the protagonists before filming begins. In implementing, Bang Carlsen then works with the techniques of narrative film – including rehearsals, directing actors, lighting and camera.

In his 1996 cinematic essay “How to Invent Reality”, he provides a blueprint for his method. Using the example of the film “It’s Now or Never” from the same year, Bang Carlsen shows how he constructed the story of an elderly Irish bachelor looking for a wife and how he selected the venues. But the protagonist Jimmy is “real” – the words that Bang Carlsen puts in his mouth could have been his own, and his life could have followed the course that the director laid out in the script.

In this way, the “staged documentaries” ran counter to everything that corresponded to traditional ideas of documentary cinema. Today, as staging plays an increasingly important role in the documentary, Bang Carlsen can be regarded as the definitive expert on this form of hybrid documentary. As before, the films evoke controversial reactions, while at the same time they have tremendous public appeal. Jon Bang Carlsen invites his audience to look closely. What do we see? The truth? Or reality? (Whose? The protagonist’s, the filmmaker’s or our own?)

He also thematically negotiates the game between fiction and reality in every film anew. “It’s Now or Never” shows the single life on the Irish coast; “Before the Guests Arrive” (1986) is a chamber drama about two women in a hotel. Also located in a hotel is the comedy “Hotel of the Stars” (1981), about the big screen dreams of two extras in Hollywood. “Purity Beats Everything” (2007) follows the story of two Holocaust survivors.

To accompany the homage curated by Matthias Heeder, Jon Bang Carlsen will present his documentary method in a master class and also bring his new book, which will celebrate its world premiere in Leipzig.” (TSM Blogpost 02-10-2014)

Jon Bang Carlsen 2014

MASTERCLASS LEIPZIG 2014

I went to the masterclass with Jon Bang Carlsen yesterday, lots of young people, who had a good time (2 ½ hour) with a director, who has been part of my professional life since he started his long career. Danish Bang Carlsen was in Leipzig because of a retrospective homage to him, 8 films, on top of that he is also a member of the main jury. The audience was spoilt with several clips and with words/sentences from the director to explain his method. Let me give you some of them: ”I don’t want to be a victim of life’s coincidences” (referring to his ”staged documentary”), ”we all become part of the landscape” (referring to his Northern Jutland background), ”I have to be able to control the visuals”, ”I love framing”, I have to find a way ”to write the visuals”, ”our personal scars give us the energy”, ”there has to be a keyhole between me and my character”, ”I find it hard to believe in pure narrative”, ”you have to make yourself vulnerable… ”Blind Angels” (2007) was made by me in a period of contemplation”, ”you have to use the stuff that happens before the brain comes in”. Clips were shown from ”Before the Guests Arrive”, ”It’s Now or Never” and the connected ”How to Invent Reality”, ”Addicted to Solitude”, ”Blinded Angels”, ”The Right Amount of Violence”. (TSM, blogpost 31-10-2014)

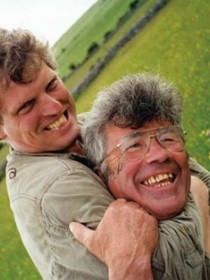

Photo by Jon Bang Carlsen from ”How to Invent Reality” (director left, main character Jimmy right).

HELE VÆRKET

FOF-Randers har også en højskole. Der havde jeg for nogle dage siden et foredrag, som noget pompøst var slået således op i aftenskolens katalog: ”JON BANG CARLSENS FILM – mellem digt og virkelighed. Jon Bang Carlsen har lavet film siden 1974. Titler, som måske huskes er ”Jenny”(1977), ”Ofelia kommer til byen” (1985), ”Før gæsterne kommer”(1986), ”Portræt af Gud” (2001), og han er stadig i fuld gang, hans seneste film er “Just the Right Amount of Violence” fra 2013. Stederne er Danmark, Amerika, Irland og Sydafrika. Jeg vil de to timer fortælle lidt om mine læsninger af hans film og nærmere introducere nogle få af dem og vise citater fra dem. Jeg vil pege på links til, hvor man på nettet kan se dem i fuld længde.”

Jeg begyndte foredraget forleden dag med at snakke om, hvor vigtigt det er engang imellem at læse hele værket, den hele Henrik Pontoppidan, hele Josefine Klougart. At se hele værket, Peter Greenaway, David Lynch, Werner Herzog og altså Jon Bang Carlsen. Udbredte mig om mine personlige oplevelser med den øvelse, belærende. Det var jo højskole.

LINJERNE

Så kom jeg til linjerne i værket, linjerne i Bang Carlsens værk. Jeg talte først om kvinderne, altid stærke, men fulde af hensyn, eller ydmyge, men stolte, jeg talte med udgangspunkt i ”Jenny” og ”Før gæsterne kommer” og ”Næste stop Paradis”, først om de ældre kvinder i filmene og ud fra den sidste og ”Time Out!” om Bang Carlsens skildringer af unge kvinder. Derefter om hans mænd, som altid er stærke og hensynsfulde eller stærke og hensynsløse. Vi så på hans steder og landskaber, som blev hans locations, Vestjylland, Sjælland, Amerika, Irland, Sydafrika. Gennemtænkningen af spørgsmålet om Gud, troen og tvivlen kunne også følges gennem værket, hvor det spidsedes til i ”Portræt af Gud”:

”Præsten: Det modsatte af tro er ikke tvivl. Det modsatte af tro er vished.

Bang Carlsen: Det var en god formulering. Kan du gentage den?

Præsten: Ja. Det modsatte af tro er ikke tvivl. Det modsatte af tro er vished. Hvis jeg følte mig sikker på Gud, ville jeg opgive min tro helt.

Bang Carlsen: Indbefatter Gud… Besidder han… Tvivler han selv?

Præsten: Det er en interessant tanke. Det tror jeg aldrig jeg har tænkt på. Jeg er sikker på – at tvivlen på en eller anden måde må være en del af Gud… Det er faktisk for omfattende overhovedet at spekulere på. Det må jeg lige overveje…”

En fjerde linje gennem værket kunne endelig være historien med krigen, nazismen, jøderne, de hvide og de sorte og det at tilhøre mordet på præsident Kennedy-generationen, som en yngre tilhører 9/11-generationen, at have desillusionen og angsten at forholde sig til, hvad den vidunderlige Jenny ikke kender til i sin generation. På billedet i åbningen ser vi familieportrætter af den alvorlige slags fra fotografen dengang. En kvindestemme, ældre, siger på vestjysk:

”Det er fredag, den anden januar 1977, og jeg føler mig sund og rask…” Portrætterne fortsætter i overtoninger, en lille pige bliver ung pige, ung kvinde, ung kone. Og stemmen fortsætter sin optegnelse. En mellemting mellem dagbog og tilbageskuende vurdering, et testamente: ”Der er sket meget i min tid…” Og den sammenligner den nye usikkerhed. Vi er i det moderne. I et kontrolrum et sted i USA, har kvinden læst, er der altid to til stede. Hvis den ene skulle bryde sammen og ville trykke på knappen, skal den anden kunne gribe ind. ”Sådan også på Cheminova , vores kemifabrik. Der er der også to, skulle den ene falde i søvn. For mennesket må selv tage ansvar og ikke give Gud skylden for ulykkerne, det selv har skabt grundlaget for…”

Og vi så klip fra ”Næste stop Paradis” (1980) to møder mellem kvinde og mand, de første blik, de gamle først. Så de unge. At leve i flere tidsaldre på samme tid, som instruktøren udtrykker det i Lars Movins imponerende og herefter uundværlige bog: ”For nok er hun en gammel kvinde, men den unge kvinde lever stadig i hende, og selvfølgelig fremkalder den nye kærlighedshistorie på plejehjemmet erindringen om den unge piges passion…”

CITATERNE

Fra ”Time Out” (1988) så vi åbningen med de amerikanske landskaber og Carl Nielsen musik, om at begynde en historie, måske en stor fortælling, med den indre monolog, som er meget Jon Bang Carlsen…, fra ”Addicted to Solitude” (1999) med det nye spor med de essayistiske film fra Sydafrika (Movin, 325). De to kvinder, den ældre og den yngre. Han fotograferer nu også selv som han altid skriver selv, men han speaker nu også selv og er næsten inde i billedet…

Vi så åbningen i ”Blinded Angles” (2007), om at flyve, om en faldskærm, som senere bliver en paraglider. Bang Carlsens speak handler om at snakke med folk, han møder en Jenny i flyet og det bliver ”en lang rejse ind i mig selv…”, men med en skuespiller, Rune Kiddes ankomst og filmen begynder med det samme med som blind at gå ind i et hus…Take efter take…

Som sidste klip så vi fra ”Purity beats everything (2007) igen en åbning. Billeder fra Sydafrika, sorte lufter hvides hvide hunde og to overlevende fortæller om rædslerne dengang under krigen i de tyske koncentrationslejre, sættes sammen med billeder fra instruktørens hjem og arbejdsværelse og vi ser, at han bor som i sin barndom, i en lille gammel gård på Sjælland, og verdens historierne glider i hans materiale fra rejserne ind gennem computeren.

LINKS TIL NOGLE AF DE OMTALTE FILM

Men det allervigtigste var, at tilhørerne blev så glade for at få at vide, at mange af filmene kunne de se gratis på FILMCENTRALEN/alle.dk i en fornem, sikker streaming (efter hvert klip var der et kollektivt suk, åh fortsæt…), og de skrev deres e-mail adresser på en liste, og da jeg kom hjem sendte jeg dem denne mail med dybe links, så de kun skulle klikke to gange, så vises filmen i fuld lægde. Imidlertid findes vigtige film som ”Næste stop Paradis”, ”Ofelia kommer til byen” og ”Time Out!” desværre ikke på Filmcentralen:

Jenny (1978) 38 min.

Før gæsterne kommer (1984) 18 min.

It’s Now or Never (1996) 45 min.

Addicted to Solitude (1999) 70 min.

Portræt af Gud (2001) 71 min.

Blinded Angles (2007) 85 min.

Purity beats everything (2007) 51 min.

LITTERATUR

Jon Bang Carlsen: Locations. Essays (2002)

Lars Movin: Jeg ville først finde sandheden. Monografi om Jon Bang Carlsen og hans film (2012)

Tue Steen Müller og Allan Berg Nielsen: Jon Bang Carlsen og hans film. Samlede blogposts på Filmkommentaren (2015). Denne tekst, som dog senere er tilføjet nye afsnit.

(ABN, blogpost 31-01-2015)

GREEK TRIBUTE 2016

The 18th edition of the Thessaloniki Documentary Festival includes a retrospective of films by Danish director Jon Bang Carlsen, indeed not the first time this director has been, much deserved, presented as one of the most interesting documentary directors of our time. A man who went “hybrid” long before this word came into the documentary vocabulary, read what he said at a masterclass in Thessaloniki:

“I have a special approach towards documentaries. I don’t exactly know what a documentary is. When I graduated from Film School – it might as well be… a hundred years ago – I wanted to look into the harmony offered by life in the countryside and so I started doing research on this story I had chosen. When I attempted to put together the shreds of the reality that I was trying to depict, I did so using free associations, but when we started shooting I got the feeling that I had destroyed the beauty of my character’s life. I came to realize that the only way to depict this story would involve a reconstruction of reality. What prevailed was the need to approach my heroine’s reality in the most honest way and as accurately as possible. From the start, I was taught by my teachers that documentaries are related to the truth, that you have to follow life through the camera and show the truth. This was not directly related to what I sought to do. Also, because I also make fiction films, I don’t see such a big difference when I make documentaries. I believe that my documentaries are similar to the way someone paints a landscape. I don’t want to shoot inside a studio, but to look outside for shreds of reality and use them to narrate the story”.

The films shown from the huge filmography of Jon Bang Carlsen was “Addicted to Solitude”, “Cats in Riga”, “Déjà Vu”, “Hotel of the Stars”, “Phoenix Bird” and “Portrait of God”.

Déjà Vu

At the upcoming DocuDays festival in Kiev, Ukraine, Jon Bang Carlsen will be present to present “It’s Now or Never”. (TSM, blogpost 17-03-2016)

MASTERCLASS KIEV 2016

I am a landscape painter, said Jon Bang Carlsen at his

masterclass at the Docudays in Kiev last night. I found it to be a perfect auto-description after having seen his ”It’s Now or Never”, that came out in 1996, and has a camera that constantly caresses the Irish green and stony fields, where the director chose to have his story take place about the bachelor Jimmy looking for a woman.

I was film consultant at the National Film Board of Denmark (now The Danish Film Institute) in the early 1990’es and commissioned this film, when Jon Bang Carlsen (together with Jørgen Leth and Anne Wivel the Danish ”auteurs” of that time) came to me with a list of film themes/stories that he would love to make into films in his original style that he himself called ”staged documentary”. Today it is almost ”menu of the day” and called ”hybrid”.

The film is wonderfully old-fashioned, the characters are lovely, the

story totally romantic, straight forward it goes with Jimmy searching for a woman with the help of a matchmaker. Shot on film, the film became a success as a documentary in Europe, and as a fiction in Asia, the director told the audience.

Jon Bang Carlsen is excellent at a masterclass. He formulates himself in an inspiring manner, he expresses doubt about what he is doing, and he does so with the humour that you also see in his films. Of course he had to show a clip from ”Before the Guests Arrive” with the two old ladies in the pension before the season starts. Of course he expressed his fascination with the landscapes in South Africa where he lived for 10 years – clips from ”Addicted to Solitude” and ”Blinded Angel”, the latter he described as ”clumsy and wild” in its style, and yet this man who has travelled the world had – he said – to return to his roots, the Danish landscapes of Northern Jutland.

The audience asked questions. One was ”what were you looking for when you were 20 and what are you looking for now as 65…”. Another complimented him for asking questions with his films and not giving answers. ”In my last film ”Déjà Vu” that is just finished a woman gives the answer to it all…”, he said at the masterclass that had a full Blue Hall in the Cinema House in Kiev.

The film was part of a Danish “High Five” programme that I put together and the Docudays festival organised – with no help from the Danish Film Institute, to my big surprise and disappointment. But that is another story..

(Blogpost 28-03-2016 by Tue Steen Müller)

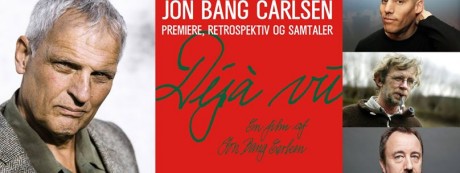

PREMIERE / RETROSPEKTIV / SAMTALER

Det er flot og fortjent og ret og rimeligt at Det Danske

Filminstituts fremragende Cinematek hylder Jon Bang Carlsen fra i morgen og frem til den 2. Oktober. Med sædvanlig redaktionel opfindsomhed har Cinematekets folk sat tre samtaler op med den danske auteur, som han bliver kaldt i omtalen af serien. I morgen skal Carlsen tale med Joshua Oppenheimer om ”Hotel of the Stars”, som instruktøren af ”The Look of Silence” mm. er helt vild med. Han er ikke den eneste. Og så vises ”Før gæsterne kommer” som udgangspunkt for en snak om ”dagligliv i Jylland” mellem Søren Ryge Petersen og Bang Carlsen. ”To af landets luneste og skarpeste menneskebetragtere”, står der som introduktion. Og så er Lars Movin selvfølgelig inviteret, ”Blinde engle” er filmen, det kunne have været andre for Movins mobbedreng af en bog om Bang Carlsens film er den man skal orientere sig i, hvis man vil bag om de mange film og rejser, som Bang Carlsen har foretaget.

A Man of the World, hvad vi også her på filmkommentaren har haft blikket rettet imod siden vi startede for snart ti år siden. Vi har skrevet et væld af tekster om Jon Bang Carlsen. Og der kommer én til snart om hans nyeste værk, ”Déjà Vu”, som har premiere i Cinemateket den 22. September.

Her er programmet:

Søndag den 18. september kl. 19:00 ‘Hotel of the Stars’ + Joshua Oppenheimer i samtale med Jon Bang Carlsen

Tirsdag den 20. september kl. 19:30 ‘Før gæsterne kommer’ + Søren Ryge Petersen i samtale med Jon Bang Carlsen

Tirsdag den 20. september kl. 21:15 ‘Ofelia kommer til byen’ – med introduktion ved instruktøren

Torsdag den 22. september kl. 16:30 ‘Blinde Engle’ + Lars Movin i samtale med Jon Bang Carlsen

Torsdag den 22. september-onsdag den 28. september: Daglige visninger af ‘Déjà vu’ – den første med introduktion af instruktøren.

Onsdag den 12. oktober kl. 16:45 ‘Ofelia kommer til byen’ (Jon Bang Carlsen, 1985)

Alt sammen i Cinemateket, Gothersgade 55, Kbh K, 33743412

(Blogindlæg 17-09-2016 af Tue Steen Müller)