Viviane Candas: A Possible Algeria

TODAY, NOW…

Viviane Candas: A Possible Algeria

by Allan Berg Nielsen / Filmkommentaren, le 4.2.2018 / Docs & Talks 2018 / translation into English: Sara Thelle

1.

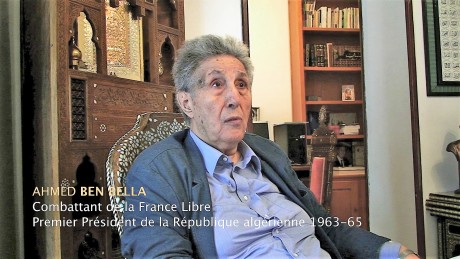

The film is built upon the voice, the director of the film’s own voice. It tells the story. I always like that, it is honest, it is literary, closer to writing. And Viviane Candas’ voice makes me feel safe and makes me listen, even though what it tells me is horrifying. Next, her film builds on the archive material, a rare collection of historical footage edited together with a private archive. I almost always like that too, at least when it is done in a poetic construction like it is here, and not as a pedantic communication of a curriculum. In Candas’ work, this material is the very connection between the history of the world, the history of Algeria, the history of France and the biography of Yves Mathieu. He was Viviane Candas’ father, French as she, but deeply connected with Algeria in the country’s fateful hour. The narrative of the film is embedded in the two lines of the title, A Possible Algeria: The Revolution of Yves Mathieu, and in the contrast between society/nation/people and the individual lies the existential drama and the reflection on the nature of identity. Finally, the film is built on Candas’ uniquely sensitive and honest interviews with a few of the story’s key figures, which in the literary spirit of the film are more searching conversations than factual question/answer scenes. The heterogeneity of this material testifies to a long-standing collection of footage for the film, and it is linked by vignettes from the research travels in a reconstruction that has a fixed visual uniformity which works as a refuge for reflection. But curiously, these vignettes do not function as the “now” of the story. The present of the film is the voice of Candas narrating, and the protagonists leading the conversation in the interview scenes, where the director’s voice is usually cut out, and yet in a strange way she is still very present. The conclusion of all this results in me really meeting these people, and the encounter with an old Ahmed Ben Bella is an emotional shock. This is the present of the film, here is world history itself present in this fragile body that speaks of itself as a socialist. Today, now …

2.

The war in Algeria was a French matter, as I remember it, and the war was the brutality of the French military. I read about Djamila Boupacha in the Danish periodical Perspektiv, a specific quote from her during the trial, her important testimony, is still locked in my memory, still shaking me, because I remember how it was with me and the knowledge of violent brutality back then. She was always Picasso’s drawing, but it was not about Picasso, it was her. She, the model imprinted on the small portrait drawn after a photograph, was stronger than the artist, in a way opposite Guernica, who was always the famous painter more than the wretched city. I read Simone de Beauvoir’s novel The Mandarins about the French Intellectual Left in the 1940s, on the circle of Camus and Sartre. And I read about the war and about General Jacques Massu and his paratroopers’ victory in 1957 over the FLN Resistance in the capital, which he tore up with arbitrary arrests and brutal interrogations and systematic torture. It was The Battle of Algiers, which in 1966 also became a film by Gillo Pontecorvo with Jean Martin in the role of Colonel Mathieu, who is probably a portrait of General Massu, a feature film in black and white documentary style with amateurs straight in from the street in most of the other roles. The mimic documentary quality of Pontecorvo’s film is so astonishing that Candas has been able to use scenes from it as part of her archive material, for example the execution scenes.

3.

The opening sequence, the first images: the bridge with the cars in the mountain landscape, the roads seen from the car, the railway station with the train on a regular day, the style of the images as a whole and their particular technical quality define the time of the film as present, right now when these images where filmed, and right now where I am experiencing it, recalling the story of Algeria’s war of independence as scattered fragments bound in the films, photographs and documents from the archives, which are consistent layers in the architecture of the film: its past.

4.

The participants in the conversations are in this now, the director’s voice is in this now, the scenes of the vignettes are this now, thereby framing everything with the present, also the layers of the archive footage, which through the superb editing work is writing the film’s past. It is the fragile images of the memory, the fragments of the past, to which the voices add details. To all the terrifying events. But also adding clarifications, about what really happened: the guillotine in the prison yard; the execution of an Algerian resistance fighter; how an exit at a main road holds the information about the way in which Yves Mathieu in all probability was murdered, a circumstantial evidence indicating that this was possible, such as the car wreck was found. It is a film about memory based on archive material more related to Chris Marker’s Level 5 (1997) written in the present of the editing room, with its minimal and indistinct but utterly decisive archive scenes and photos; and it is related to Emile de Antonio’s Millhouse (1971), made solely on archive clips and, as I remember it, written in the past tense as a form of serious entertainment, while Chris Marker’s film is a moral philosophical task in the present tense, precisely like the core of Viviane Candas’ oeuvre, which is a similar obligation for me, a challenge to my thoughts, precisely what the festival Docs & Talks where the film is screened is intending.

5.

Candas’s film does not document this brief but violent chapter of Algeria’s history, rather her film is documenting a qualified thought about this period in history, a thought qualified by the memory of a state leader, the memory of a minister, and a daughter’s remembrance of her absent father. She now needs to share their memories, in order to understand her well-ordered fragments as historical knowledge, to come to love her revolutionary father, who was far away and buried in work, understand him and love him unreservedly now, despite him having been dead for many years. She stands in the present with the plate with the grave inscriptions in her hand, considering the right lapidary summary of this person’s life.

6.

The subtitle of the film is La révolution d’Yves Mathieu as I read on the screen after the title sequence. This is a couple of days ago, and I only now begin to understand the importance of the title as a whole. I am ready to watch this remarkable film again, ready to listen to Rasmus Alenius Boserup’s introduction and to his conversation with Viviane Candas in Cinemateket at the Docs & Talks Film and Research Festival.

Photos: Yves Mathieu and Ahmet Ben Bella

http://www.filmkommentaren.dk/blog/blogpost/4151/ (Filmkommentaren, le 4.2.2018)

DOCS & TALKS 2019

DIIS OG CINEMATEKET / FILM- OG FORSKNINGSDAGE /

31. JANUAR- 6. FEBRUAR 2019